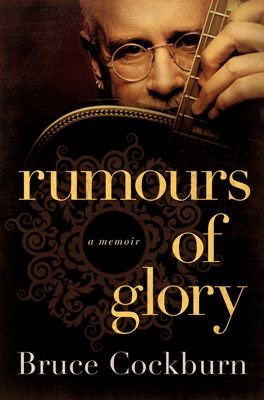

Rumours of Glory

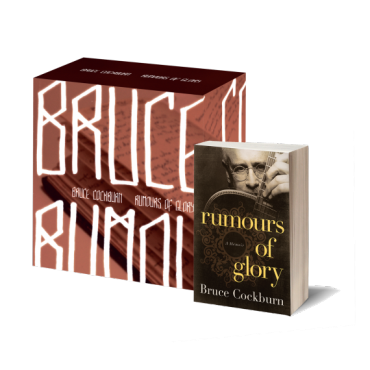

Bruce's official memoir was release on November 4, 2014. It is published in hardback by HarperOne and is 544 pages long. It includes pages of both color and black & white photos and a discography.

It can be purchased at Amazon, iBook Store and other online retailers.

To compliment the memoir, True North Records released an eight CD, one DVD box set. Seven of the CDs contain all the songs referenced in the memoir. One CD contains previously unreleased tracks and tracks that were released on various artists compilation CDs. The DVD, Slice O Life, is comprised of nineteen live tracks form three solo shows in May, 2008, in Massachusetts and New York State.

Press Release Here - Preview Chapter 4 Here - Preview Chapter 11 Here

Here you can find a PDF of the 90 page booklet insert for the CD/DVD box set, Rumours of Glory.

BOOK EVENTS

October 17, 2014, San Francisco, CA

Litquake Festival 2014

November 5, 2014, Toronto, ON

Toronto Public Library

Interview with Peter Howell (bookseller: Ben McNally Books)

November 8, 2014, Ottawa, ON

Kanata Indigo, signing

November 9, 2014, Montreal QC

Paragraphe Books and Brunch series

November 10, 2014, Vancouver, BC

St Andrew’s Wesley United Church

Interview with Hal Wake (bookseller: Kidsbooks)

Sunday, November 16, 2014, Mill Valley, CA

Sweetwater Music Hall Presents

November 19, 2014, Berkeley, CA

Berkeley, CA - Radio KPFA Presents

Interviewer: Luis Medina, Music Director at KPFA

December 4, 2014, Highlands Ranch, CO

Tattered Cover Bookstore

March 5, 2015 - Belfast, Northern Ireland

The Holiday Inn - Bookreading and interview

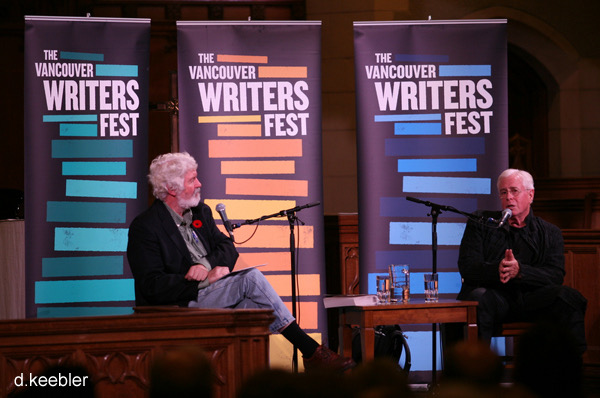

November 10, 2014: The Vancouver Writers Fest. Bruce was interviewed by Hal Wake at St. Andrew’s-Wesley United Church.

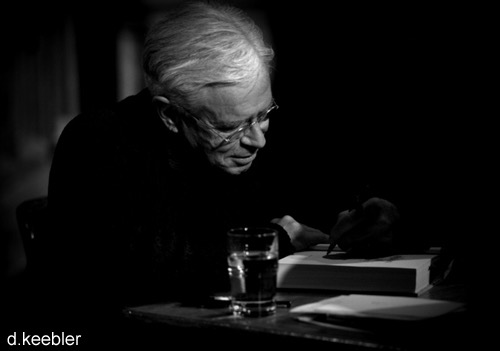

Interview, audience questions and book signing. Use of photos by permission, please. Contact me here.

MEDIA REVIEWS, ARTICLES AND INTERVIEWS

Posted February 20, 2016

Mark Dunn reviews Rumours of Glory for the Literary Review of Canada. You can read the review here.

April 22, 2015

Real Change

World of Wonders

by Joe Martin

Book Review - Rumours of Glory, a Memoir by Bruce Cockburn and Greg King

“I honour nonviolence as a way of being, and as a political tactic, but I am not a pacifist. As we continue to watch the world’s greatest military powers plunder weaker states and people as an integral, almost pro forma method of planetary domination, it’s clear that a violent response to such injustice, and carnage, would be useless and ever more destructive. But that’s easy for me to say as I sit on my peaceful deck in my peaceful city in my relatively peaceful country.”

“I honour nonviolence as a way of being, and as a political tactic, but I am not a pacifist. As we continue to watch the world’s greatest military powers plunder weaker states and people as an integral, almost pro forma method of planetary domination, it’s clear that a violent response to such injustice, and carnage, would be useless and ever more destructive. But that’s easy for me to say as I sit on my peaceful deck in my peaceful city in my relatively peaceful country.”

So writes the gifted Canadian singer, song writer and guitarist Bruce Cockburn in his recent memoir, “Rumours of Glory.” An intrepid world traveler and human rights activist, he has journeyed to dangerous war zones and scenes of hideous human travail. In 1983, under the auspices of Oxfam, Cockburn went to southern Mexico to observe the living conditions of impoverished Guatemalan citizens who had fled to refugee camps near the Guatemalan border.

Cockburn was shocked by the stench and destitution. The displaced had fled the murderous policies of their country’s regime, its brutal soldiers trained and funded by the United States. “The Guatemalan military wasn’t content to simply torture and slaughter and destroy villages where they were. They continued to harass the survivors, crossing the border into Mexico and attacking the refugee camps, strafing from helicopters, now and then dragging people off to the jungle and hacking them to pieces with machetes.”

Cockburn wrote “If I Had a Rocket Launcher” in response. The final verse of this powerful song highlighted his outrage: “I want to raise every voice—at least I’ve got to try. Every time I think about it, water rises to my eyes.”

Cockburn had grown up in a comfortable middle class family in Ottowa. His family’s dynamic tended to stifle emotional communication. To this day, Cockburn is inclined to introversion and solitude, a self-titled “emotionally cloistered chameleon.” This internal orientation and frequent traveling has contributed to a string of broken marriages and relationships.

Early in life, he expressed a passion for music. He had little interest in the rest of academia. For a time in the mid 1960s Cockburn was a student at the Berklee College of Music in Boston. The city then was a center of the folk music scene. Cockburn left Boston before he obtained his degree, returning to Canada to pursue music in his own way and immerse himself in the Canadian music scene: “Here’s the door. There’s the cliff. Go through. Jump. Just don’t forget your guitar,” he writes.

Cockburn writes of his interest in spirituality. His first wife inspired him to revisit the deeper dimensions of Christianity, though he remains “leery of the dogma and doctrine that so many have attached to Christianity as well as to most other religions.” Cockburn’s attraction to things spiritual and mystical surely influences his laid back and critical approach to the venal side of the music industry. “Commerce, in an era when the market has become god, can derail our quest for the Divine.” Cockburn admits his perspective has sometimes driven his manager Bernie Finkelstein to distraction, yet their partnership has endured for decades.

Cockburn’s political consciousness came about gradually. He was becoming more aware of greedy corporations wreaking ecological devastation in his native country. Mercury contamination especially stirred his sense of urgency, as it combined environmental destruction with the deepening economic horrors overwhelming the world’s poor.

Around the globe, Cockburn has witnessed manifold aspects of planetary crisis. While concerned individuals and organizations of goodwill remain hopeful harbingers of positive change, the sheer magnitude of natural resource erosion and social dislocation is daunting. Too many in the developed world remain indifferent or oblivious. Referring to his song “The Trouble with Normal” Cockburn writes: “Each sliding step down this road brings cries of warning and expressions of dismay. Each new skid downward leaves the previous one seeming acceptable after all. That, indeed, is the trouble with ‘normal.’”

Cockburn has championed the effort to rid the world of land mines, which are still in many countries: Egypt, Iraq, Mozambique and Cambodia to name a few. “At least sixty million are still buried across the globe, including a staggering twenty-three million in Egypt alone (more than any other nation), alongside unexploded ordnance left from World War II, disallowing use of huge regions in the north and east of the country,” he wrote.

Wherever he finds himself in the Third World, Cockburn jams with local musicians. These encounters can open new musical horizons.

His book is an honest and compelling memoir. Those unacquainted with Cockburn’s substantial oeuvre can find plenty of songs and performances on YouTube. The book and his music taken together present Cockburn as an indisputably accomplished artist and also one of the great humanitarians of our troubled time.

Illustration by Jon Williams, Real Change

No Depression

December 21, 2014

Bruce Cockburn - Rumours of Glory (Book & Album Review)

by Skot Nelson

“None of us,” Bruce Cockburn writes near the end of his newly released autobiography, Rumours of Glory, “has the capacity to stand far enough back from the picture to see how the parts of our lives intersect. We’re all tiny figures in the jigsaw flux."

In music circles, a cry of Bruce! will probably, most often, lead the listener to infer Springsteen as the implied last name. There’s a huge contingent of music fans, though, for whom the name is equally likely to evoke Cockburn. In some contexts, the latter might be the first to come to mind.

Cockburn’s reputation as a songwriter has long since passed to legendary status. It seems fitting in a world where a barely 20-year-old Justin Bieber publishes a “memoir” that a man with Cockburn’s lasting power and influence pen one too. If there is any mercy in the world, the latter will outsell the former.

Cockburn’s look at the picture of his life is extensive and full of well-told pieces. The book is a framework in which the singer tells the origin tales of many of his songs, and those lyrics appear here as well. To accompany the book, the legendary True North label has released a 9-CD box set (including a disk of rare and previously unreleased material) of the same name as a sort of accompaniment to the book. All told, the book and compilation paint an extensive portrait of Cockburn’s life in and out of music.

Rumours of Glory, the book, doesn’t see Cockburn shy away from his reputation as a political activist. The book is more than a chronological romp through his career, and if you’re not familiar with the politics of Central America the book will serve as a decent overview of the last thirty years or so. Cockburn reminisces about many trips to that region with various non-governmental agencies, and makes it clear that he was not a fan of pretty much any U.S. president from Reagan onwards. He tells the story of playing a Clinton victory party with Roseanne Cash where, for him, the most exciting moment was being introuduced to both Jonny and June. The smile on his face when Johnny shake his hand fad says “Nice playin’, son,” practically beams from the page.

Sadder is his description of a visit to Cambodia’s Tuol Sleng, a high school that was used by the Khmer Rouge as a toture site during their horrific reign. “Tuol Sleng is a black hole that sucked all human goodness into it, leaving an event horizon of pure evil that chills the heart of everyone who goes there."

Cockburn does a nice job of telling the tales behind songs he’s written. “What doesn’t kill you makes for songs,” he says in describing a year long hiatus he took from performing which led to some fruitful songwriting. He describes the subsequent album Breakfast in New Orleans Dinner in Timbuktu as reflecting “…in a time-lapse manner, the slow unfurling of a life…” and book behaves in much the same way.

Not much seems to be held back. There are stories of relationships pursued and lost, of working with T. Bone Burnett, of a daughter whose life as a teenager seemed to be spiralling out of control (but soon regains its path), and of visits to war zones. Cockburn lays the trials of his life on the page and the result is a compelling read for any fan of songwriting.

The 9-CD of the same name released by True North records contains 117 of Cockburn’s songs in addition to a DVD of concert footage recorded in 2008 an extensive book of liner notes. Each set is autographed and numbered, which means that, if you know a Cockburn fan, there’s probably not a better gift to get them.

More importantly, the box stands as a comprehensive document of one of the most compelling careers in mainstream music. Its collection of songs ranges from the obscure to the well known and in doing so it achieves more than just being a greatest hits collection (of which there have been several released already). The disc of unreleased material includes a Gordon Lightfoot cover as well as selections from Cockburn’s soundtrack for the NFB film Waterwalker. As usual with an artist of this caliber and integrity, it’s amazing to listen to the stuff that wasn’t good enough to make an album at times.

As a songwriter, Cockburn is almost without equal. His output rival’s Dylan’s in its quality and is arguably better in its consistency. 1979’s Wondering Where the Lions Are remains the greatest song to ever come out of Canada (and the only one, he posits, to ever make the Billboard Charts with the word ‘petroflyphs’ in it) but it’s rivalled by later career works like Last Night of the World and Pacing the Cage. Despite having recorded 31 albums, Bruce hasn’t lost his passion for what he does and that shows in his recent output. Rumours of Glory as both a book and a music compilation is a long overdue capsule of a career.

December 9, 2014

Rolling Stone

The 'Rumours' Are True: Bruce Cockburn on His New Memoir

by Garrett White

When many artists visit New York, they stay at downtown hotels like the Mondrian or the Bowery. Bruce Cockburn stays nearby at the Soho Holiday Inn. In town to launch his new memoir, Rumours of Glory, with a concert and book signing, the iconoclastic singer-songwriter arrives in the lobby wearing a modest outfit of black pants, black combat boots and a long black coat.

"This is not your standard rock & roll memoir," Cockburn writes in the book's preface. "You won't find me snorting coke with the young Elton John or shooting smack with Keith Richards." So what do you find? "I suppose it's about growing up," he says, ordering a glass of wine in the lobby bar. "It didn't require a decision to expose myself in the book, especially because the mandate was to write what the publisher was calling a spiritual memoir."

"This is not your standard rock & roll memoir," Cockburn writes in the book's preface. "You won't find me snorting coke with the young Elton John or shooting smack with Keith Richards." So what do you find? "I suppose it's about growing up," he says, ordering a glass of wine in the lobby bar. "It didn't require a decision to expose myself in the book, especially because the mandate was to write what the publisher was calling a spiritual memoir."

Rumours opens with the 69-year-old's awkward but comfortable childhood and covers his formative years in the Sixties folk-rock scenes in Ottawa and Toronto. In early bands, he opened for Cream, the Lovin' Spoonful and Jimi Hendrix. "I asked an audience recently if they wanted me to read about the origin of 'If I Had a Rocket Launcher' or meeting Jimi Hendrix," he says between sips. "Everybody yelled out 'Hendrix!'"

During an 18-month stint at Berklee College of Music, Cockburn was more interested in writing poetry than transcribing scales, but he soon developed his signature style – "a combination of country blues fingerpicking and poorly absorbed jazz training" – by using his right thumb to carry the rhythm and his fingers to play melody. "Mississippi John Hurt and the old blues guys were the musicians I admired when I was young," he says.

The music Cockburn made during this period can be heard on Rumours of Glory's accompanying box set, a 117-song collection sequenced to parallel the book to allow the reader to hear the evolution it describes. One major turning point: the 1976 album In the Falling Dark, which marks the beginning of Cockburn's turn away from traditional Christianity and toward the all-inclusive mysticism he professes now.

"It was apparent fairly quickly that I didn't belong in that camp," he says of his time in the church. "I couldn't be that literal about things. I couldn't accept myself as a fundamentalist, and that meant moving in a more mystical direction." Yet even in his explicitly Christian phase, he aimed never to be an ideologue or proselytizer. "Nobody has to do anything," he says. "God offers freedom, as far as I understand it."

This evolution has profoundly affected not just generations of fans but some of the most important songwriters of our time. Graham Nash calls Cockburn "the consummate troubadour, a musical hero to many who are trying to make the world a better place," and Jackson Browne tells Rolling Stone that "few songwriters have been able to express as coherently the impulse for justice and the quest for moral equilibrium." To Bonnie Raitt, he is "a huge inspiration."

In recent years, Cockburn's spiritual odyssey has come to include even Jungian-based dream therapy. "That's what gave me the image of Christ as a collective animus," he says. "But is he more of a collective animus figure than Buddha? I don't think so." The dream therapy has also led to an interest in neuroscience and the nature of consciousness. "The idea of God as the boundless, as an undefinable and in a certain way unapproachable being except by proxy, has a lot of validity," Cockburn says. "That means sometimes he's going to seem like a hallucination or a motivator of things we don't really want to see. There's a juicy element of chaos about that, and that's where I tip over into 'I don't have a clue.'"

He continues: "Why are we different from raccoons? We believe we're special, historically and by nature, but who knows how raccoons see things? In some universe, parallel to this one, raccoons may be running the place. That's a nice thought. None of us knows shit from Shinola, and the people who claim they do know are grasping at straws – or worse."

Accordingly, a good deal of this self-described loner's later music brims with ecstatic emotion: "When I play music and my mind goes away from my ego and from my day-to-day concerns, I become more open to the Divine. I'd love to be in an ecstatic place all the time. It would feel a lot better than how I feel most of the time – that's the point of singing hymns in church. The snake handlers get that. Ecstasy is good, but I don't want to be bitten by a rattlesnake to get ecstatic."

Beyond belief systems (or lack thereof), the Rumours of Glory book and box set offer a call to life, embracing the mysteries of existence and the search for love and beauty, wherever one finds it. Part of that, of course, is a fine meal now and then, even if it's eaten in the bar at a Holiday Inn. Following the wine, Cockburn orders a burger: "Just right."

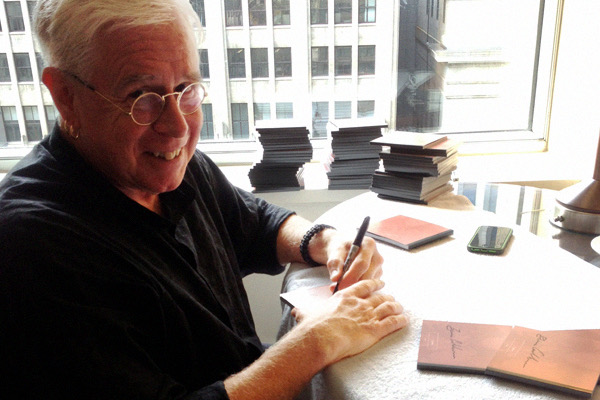

Photo: Linda Panetta. Bruce in New York City on November 4, 2014

December 5, 2014

The Toronto Globe & Mail

Rumours of Glory: Bruce Cockburn’s memoir proves he’s as fierce in print as on stage

by Brad Wheeler

I doubt Bruce Cockburn has ever even read a rock and roll memoir, so when he opens his own with “this is not your standard rock and roll memoir,” he probably hasn’t a clue. Because such autobiographies come in all tones, rhythms and degrees of disclosure, sensationalism and cocaine residue.

But then, this: Cockburn’s Rumours of Glory is not your standard rock and roll memoir.

Nor should it be. Written with help from the American journalist Greg King, the more than 500 pages are candid, unbreezy, opinionated, contextual, political, not always entertaining but always important. These are the accumulations of an intricate and self-aware man. And while one might not hang on to every story or song explanation, nothing jumps out as being extraneous.

Why read Cockburn’s story? Songwriters come and go, but take my advice when I tell you to pay attention to the spiritually seeking, war-zone-visiting, guitar-mastering Canadian ones who hold rocket launchers.

Or the ones who, because monsters were beneath his bed, slept as a child with a toy revolver and a rubber knife under his pillow. And the ones who as adults “kick at the darkness ’til it bleeds daylight” with a left foot, as we learn on page 12, that is two sizes larger than his right. Oh yeah, there’s a lot going on with this guy, and much under the skin of the Ottawa-born son of a radiologist.

I’m told by his longtime manager – Bernie Finkelstein, who is treated in the book with respectful, favourable (if occasionally bristly) appraisal – that Cockburn has a wry sense of humour. There’s not enough of it here. Some of it, though, comes out in an excellent, honest paragraph about his first wife Kitty and her reasonable wish in the mid-70s to have a child with her husband:

“I did not share her enthusiasm for the project, but I believed her and was committed to her, so I went along. … In due course a beautiful baby was born, though it took a day or two for the beauty to shine through. I got in trouble right away for remarking that she looked a bit like Idi Amin. Well, what the hell – she did.”

He goes on to explain that newborns always have the look of old people who are unhappy to be back in the world, but that the look fades. To get himself out of a trouble he then offers the lyrics of a song that explains his love for his offspring, written while she was in utero. The tune is Little Seahorse: “Swimming in a primal sea, heartbeat like a leaf quaking in the breeze… I already love you, and I don’t even know who you are.”

Lyrics are offered throughout, as a way of connecting his music with his life. You might already know that the words to his 1984 hit If I Had a Rocket Launcher came to him in a Mexican hotel room after witnessing atrocities during a visit to a refugee camp in Guatemala. His war-zone journeys are covered in detail here.

You might also know that after he “found Jesus” in 1974, Cockburn’s spiritual notions have made their way into his music. “I have attempted to live my life somewhat in line with his Word, without necessarily taking it as, well, gospel,” Cockburn explains in the book’s forewarning over ture. The word “Divine” is featured more times in Rumours of Glory than any book not written by King James or John Waters.

Cockburn doesn’t consider himself a preacher or a protest singer, but an observer who “paints sonic pictures of what I encounter, feel and think is true.” It’s intense stuff, from an intense artist and human.

Where James Taylor has seen fire and rain, Cockburn has sought it out. As a songwriter and a guitarist, he brings a rocket launcher to a knife fight. Some think his manner is too serious or over-killing or maybe even unfair. But I say styles make the fight – and the rock and roll memoir.

December 2, 2014

The Record

Bruce Cockburn’s manager will launch star’s book at Princess

by Robert Reid

WATERLOO — The book launch and film screening at the Princess Twin on Dec. 11 is unique for a couple of reasons.

First, while the UpTown Waterloo cinema present live concerts as well as screens films, it seldom hosts book launches, which makes "True North Talks" something of a special occasion.

But there is a twist which leads us to the second point. Although the event is subtitled "Bruce Cockburn Book Launch," the author will not be present.

Instead, True North Records founder and longtime Cockburn manager Bernie Finkelstein will be on hand to discuss his most successful client's autobiography "Rumours of Glory."

He also will introduce his own memoir, "True North: A Life Inside the Music Business," a chronicle of the folk music revival of the 1960s and the emergence of one of the country's seminal independent recording companies.

"We're excited to present (this) legendary manager," Princess co-owner John Tutt said in a release.

Finkelstein, an iconic figure in Toronto music since the 1960s, will be joined by director Joel Greenberg who directed and produced the Cockburn docudrama "Pacing the Cage."

Greenberg will offer a sneak preview of his never-before-screened concert documentary of Cockburn's 2008 "Slice o' Life" solo tour.

"The evening promises to be a celebration of all things Bruce Cockburn," Tutt confirmed.

The screening will be followed by a question-and-answer session and book-signing.

In addition to the two memoirs, Cockburn's "Rumours of Glory" autographed, limited-edition, nine-disc, DVD boxed set will be available.

The memoir and DVD package constitutes a comprehensive career retrospective for the 69-year-old singer/songwriter.

He began writing the book three years ago when he became a father for the second time. His "chronicle of faith, fear, and activism" is more than a personal history. It takes readers on a cultural and musical tour through the last half century.

Cockburn's very public life has been shaped by politics, protest, romance and spiritual exploration, which he has given expression through 31 albums that have won him critical acclaim and an international following.

The $10 general admission price includes a 10 per cent discount on the purchase of the two books and box set.

November 17, 2014

Huffington Post

Bruce Cockburn: How The End Of A Relationship Led To Dream Work

by Howard Kerbel

Bruce wanted to include "Leaving My Father's House : A Journey to Conscious Femininity" by Marion Woodman in our conversation. Just for some background, Marion Woodman is a Jungian analyst and her book reflects on the process required to bring "feminine wisdom to consciousness in a patriarchal culture" as told through the personal journeys of three women.

Howard: This book had a great impact on you. How did you come to find it?

Bruce: It goes back to the early 90s. I fell in love with someone who was married. I was with a partner at the time. It was very inconvenient but deeply passionate. And shockingly so in a way. I was approaching 50 and somewhere around that point in your life the stuff you haven't dealt with tends to surface and there's a sense of a need to settle accounts with yourself, with your past.

We had reciprocal feelings, although she not as deeply as I, and in the end we decided we wanted to stay with the people we were with so we parted company. But I found this whole process very de-stabilizing. It caused a major shakeup in many of my assumptions.

I never saw myself as a guy that would be involved in this type of thing. I had certainly been in love with and loved by a few different women over the years but always thought of myself as monogamous. This went beyond all of that in terms of the need that I felt for this person.

I felt that she was the missing twin with the other half of the ring.

She recognized that I was projecting all the stuff that I wanted to be true about myself onto her. She suggested I take a look at "Leaving My Father's House."

Howard: You mentioned she recognized you were projecting onto her what you wanted to be true about yourself. Did this start you on a path of working through those things?

Bruce: Well yes...it made everything a question. I thought I was who I was and clearly there was so much going on under the surface that I hadn't taken account of. It was the beginning of a long process that is still going on. I coincidentally started having dreams that reflected some of this stuff -- I mean they were nightmares. The archetypes that appeared in my dreams appeared in a kind of demonic form because I wasn't ready for their guidance or for them to be present in my life -- so I was running from them all the time.

Later in the 90s, I started working with a Jungian-based therapist named Marc Bregman, using the language of archetypes to help me understand what was going on. It profoundly shaped the last couple of decades.

Howard: Did you dream vividly prior to working with your therapist and recognize these archetypes before this situation? Or was this the trigger point for that?

Bruce: A little of both. I have always been interested in the various attempts by humans to interface with the Divine. Shamanism for instance relies a lot on dreams. I never had shamanic dreams that I was aware of except for one or two where the symbolism was really blatant.

I remember vaguely a dream from sometime in the 70s. I was in one of my early childhood homes as an adult and there was an enormous crimson bull and a golden lion. The bull gored me and the lion ate me. You wake up from a dream like that and think,

"Ok, well if I never read anything about comparative religion or Shamanism or anything like that I wouldn't know what to make of this but it was clearly symbolic of something."

I just didn't know what.

I have had other kinds of disturbing dreams -- all sorts. I've had dreams where I was killing people. As a kid I had dreams about monsters and dinosaurs all the time, scary things. After reading Marion Woodman I started having a context to put them in.

I had another dream where I was in a rickety old house that was invaded by demons from the basement and I was hiding in the attic walls. It's almost textbook -- out of that line of psychological thinking where the house is you and your personality and all this suppressed stuff is coming up from the basement. I started to understand the dreams but it wasn't until I began doing the actual dream work and consciously pursuing that with a guide that it really fell into place.

The dream that prompted me to go into the dream work was one I had in which I was kidnapped by this gang and sequestered in an apartment. They weren't threatening me but I was a prisoner and at one point the ringleader came into the room and said:

"I'd advise you not to drink so much."

And I woke up thinking -- that is so weird -- here's this guy telling me not to drink so much and he's right, I shouldn't drink so much. Am I being told by my subconscious I'm going to hurt myself? I guess that's the obvious conclusion but ...that guy was obviously an animus figure and it was typical of all of the dreams I had in the beginning of this process.

Anytime the animus appeared he was scary. The anima, not so.

I mean the anima was getting more loving and encouraging and occasionally outright sexy but the animus was always scary.

Howard: Looking back now on when you met this woman in the early 90's, have you been able to better understand what was driving you to behave in a manner far different than who you believed yourself to be?

Bruce: It was a multi-layered thing. On the one hand she was very attractive and nice so there was an immediate affection that developed and an attraction that was of the normal kind. But when I found out it was sort of reciprocated-we were in a situation where we had time to spend together-it just sort of snowballed. Her relationship was a bit on the rocks and she was looking for something -- really I have no idea what it was that she needed or thought she might find with me, but there was that side of it.

Howard: So almost like a mutual need?

Bruce: Yes and I didn't understand how to deal with the intensity of the feelings. I know I was now ready to experience this stuff. Though there was love in our household growing up, it was a culture where feelings were never mentioned and so I didn't have any model for expressing love. I was learning by trial and error through the various partners I had.

But I guess when I met her I was just ready to be kicked open.

Howard: I think what you just discussed are actually feelings that many people have. The way you are raised, the ways parents encourage (or don't) expression. In many cases, where the home doesn't provide a foundation to express, the feelings become muted and secondary. And then transitioning into adulthood, there is the struggle of how to experience and share them. I think it is quite common. That's interesting.

Bruce: I think it is very interesting. Certainly for us Anglo-Saxons anyway...and you grow up as a male trying to be socialized with whatever values are attached to the cultural concept of masculinity.

In my case it resulted in an inability to express myself and I was mostly unaware of my own feelings. I was carrying all kinds of baggage that I had no idea was there because if it's constantly devalued, if you're constantly prevented from acknowledging or expressing it, then after a while you just go numb and there's all that stuff happening underneath the floor down in that basement that you have no idea about.

Howard: Was the art of writing and making music a way for you to express your feelings in a different way -- to be more involved with them?

Bruce: Yes but I don't think I was very conscious of that. Obviously you could express anger for one thing. But also just love and a sense of beauty -- which is a kind of one-step-removed manifestation of some of the feelings we carry around.

Howard: How have you been able to apply what you've learned in raising your own kids?

Bruce: When my first daughter was young, the understanding I had of things was simplistic. What I knew was I didn't want to inflict the kind of rule-based worldview that I had been given on her. Her spirit should be allowed to be free. I didn't really understand how much or what that meant because I didn't really understand how much mine wasn't free.

But this was a very common sentiment at the time in the 70s. We didn't want to bring our kids up with all the crap our parents had handed us so we tried to avoid that by imposing fewer rules. I think even if you don't believe in them it's a good idea to impose some rules that you are willing to have broken.

I hope to be able to apply all of these principles with my new baby and I think to a greater extent I have a much larger ability to express love than I had in the 70s.

Howard: Based on what you have been able to bring into your life in terms of a focus on learning and evolving, and all the dream work, are you able to take things as they come or are you always trying to put them into a package or a construct to gain an understanding?

Bruce: That's an interesting question because I'm not sure that those are opposites. By nature I have a tendency to want to understand and file things away but my experience has told me that something one does with a degree of nonchalance reappears later on and needs to be reexamined. And often the things you think you understand you find out you don't at all.

I think I see somebody being a certain way and once I get past whatever emotional reaction that produces, I start thinking about what might be prompting them to be doing the things they are doing and I come up with an answer. But it's good not to be attached too closely to that answer.

Howard: Yeah I love what you just said. The fact that you still have to react as a human being to what you are witnessing emotionally and then take it to the next level and try to figure out what it all means. That is interesting because judgment is sometimes such an easy trap to fall into.

Bruce: It's not something I imposed on myself - it's something that just grew out of a deepening understanding of my own processes and the degree to which those processes are similar to other peoples. I have become more tolerant of a lot of stuff I suppose, but I still get mad about things and offended and hurt by certain kinds of behaviour.

Howard: It's a discipline not to live your life making assumptions. I fall down all the time. I walk away and say "Why did I just do that? I shouldn't have been that reactionary."

Bruce: It's kind of Jungian-based and quite Shamanistic -- I mean not in a new age sense at all but it's all about God and not everyone wants to go there.

Howard: God in what way?

Bruce: I don't mean in the religious sense but the God that we're meant to have a relationship with who is much more of a father figure than I was willing to allow for.

Howard: Can you tell me more about that?

Bruce: When I first started doing the dream work I said "No, don't give me that crap about God as a father -- I'm not interested." The first time I went to my therapist he heard what I had to say about what's going on in my life and he said: "Well, it sounds like you have father issues," and I said, "Come on -- is that the best you can do? Father issues? Everyone has father issues. That's not it!"

But it was.

I mean in the deepest sense because there's God the father -- I mean my father's a good guy but he laid some stuff on me I didn't need and as a result I have trouble relating to God as a father figure but when you go through the dreams it is.

It's not a goddess. It's a guy.

Maybe for women it's not, I don't know. I can't speak to that because I don't know how this works but I am told for women it is different. But anyway, it's all based on our own electrochemical processes. With respect to the Divine, I think there is a cosmic presence that can only reach us through the electrochemical workings of our brain.

Howard: I can't remember most of my dreams. I know they are there but I keep thinking there's something blocking them. They don't happen in any meaningful way that allows me to be circumspect around them and I can't figure it out.

And that frustrates me because they are supposed to be the windows to our souls!

Bruce: We each have our own issues with that stuff. I only remembered the most horrendous nightmares of all the dreams I had for a while. I've been doing dream work for a long time now, since the latter part of the 90's and I go through periods of months sometimes where I have very few dreams that tell me anything. But other times, and especially when I first got into it, I was shocked how fast it started to work.

I think it really makes a difference to have a guide with this because I'm not sure you can just start interpreting your dreams. I mean, maybe you can - I couldn't because I had no basis for assessing anything that had happened.

Howard: I am fascinated by the dream work. I am sure it involves all kinds of analysis. What type of work is involved?

Bruce: My dream work involves a lot of homework which consists of taking a theme from the dream and its attendant feelings and just going there for ten seconds three or four times an hour each week until the next session.

And the dreams change. And it's this process that changes the dreams. It invites more.

I mean I have had dry spells and stumbling blocks but eventually it all clears and flows again. It was an amazing discovery in the beginning to encounter that!

Howard: Thank you for the introduction to Marion's book. I learned a lot. And you have given me lot to think about. I had not been exposed to the ideas of dream work and knowing my struggles to remember mine, never mind interpreting them, it might make for an interesting next step for me.

Bruce. I enjoyed talking with you as well.

For more about Bruce and his new memoir "Rumours Of Glory" and it's companion Box Set please go to Bruce's Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/officialbrucecockburn

November 10, 2014

The Canadian Press

Bruce Cockburn's weighty new memoir explores God, guns, war, love

by Nick Patch

TORONTO - Bruce Cockburn started writing his mammoth memoir "Rumours of Glory" just as he was becoming a father for a second time, at the age of 66.

It meant for a bleary-eyed time.

"There kept being deadlines and deadlines created incredible stress, especially measured against trying to find time to write with our little daughter around," Cockburn, now 69, said during a recent interview in Toronto.

"She's about the same age as the book right now. It was unfortunate timing from the book's point of view that Iona was born when she was. Or perhaps it was good timing, maybe."

He's not sure, or maybe he's just tired. This weighty tome sure seemed to result from a difficult birth.

The decorated folkie and dedicated activist spent years stitching together this book, which dutifully traces his childhood (mostly spent around Ottawa), his hard-cleaved climb in the industry, his thorough exploration of the world's war-torn regions and his ever-evolving spiritual identity.

The decorated folkie and dedicated activist spent years stitching together this book, which dutifully traces his childhood (mostly spent around Ottawa), his hard-cleaved climb in the industry, his thorough exploration of the world's war-torn regions and his ever-evolving spiritual identity.

The very first paragraph, however, focuses on what the sprawling book is, in fact, missing.

"This is not your standard rock-and-roll memoir," he writes. "You won't find me snorting coke with the young Elton John or shooting smack with Keith Richards."

And Cockburn has many reasons for his apathy to wild industry yarns, both pragmatic and creative.

"I don't have that many stories like that to tell, and even if I did, I wouldn't tell them because I've got a green card in the U.S. and one of the things they ask you is if you have ever been involved in anything criminal," said Cockburn, based now in northern California.

"I'm not going to talk about things I was present at that people that are criminal."

He also recalls taking in a recent live reading of someone else's book, which documented the misadventures of some '70s "metalloid" act.

"It just went on and on and on. Every second word was" the F-word, he explained. "After a while, it's like, I don't care about that anymore. I'm tired of hearing about these idiots.

"But you know," he added, "I haven't lived like that. I don't know anybody who has personally. People's sexual escapades, I haven't been part of that kind of stuff either. No orgies or anything like that. To my great regret."

Cockburn does explore his life's relationships with probing curiosity, including his previous marriage to Kitty Cockburn (he has daughter Iona with wife M.J. Hannett).

Some of these disclosures might have troubled those involved. For instance, he writes about his older daughter, Jenny, and her teenage tendency to disappear for days into seedy segments of Toronto. But Cockburn said there were no issues.

One story he did feel he needed permission to tell centred on his first wife, who was apparently so distraught over the deteriorating state of their relationship, she fumbled to open the window of their third-floor London hotel room with apparent intentions to jump, before Cockburn pulled her back.

"She didn't even remember it," he said of contacting her for consent. "But she said, 'Oh, you know, it's OK, whatever.'"

Cockburn's quest for God is the thread that unites everything. Once considered a Christian artist, the 12-time Juno winner doesn't identify that way anymore.

"I don't disown it either, though," he clarified. "Which I guess makes me a complete namby pamby traveller from a hardcore Christian point of view, but ... I had trouble with the imagery (of the Bible) and with the historicity of Christ, really.

"(So) I stopped calling myself a Christian. But I might change my mind on that in a year or two years or whenever."

In other words: to be continued.

Similarly, the latest chapter in Cockburn's life — his expanded family — is actually granted only a brief epilogue in his book.

Perhaps it feels the "If I Had a Rocket Launcher" songwriter has simply started a new tale entirely.

"(My life now) would have required at least a couple hundred pages and it was already too long," he said. "But it was more because I don't know where it's going. It's going in a good direction and it has been from the start, but I don't know the story yet.

"It's too new and too much still unfolding."

Photo: Nathan Denette

November 8, 2014

Winnipeg Free Press

Great big love

Cockburn mines music, politics, spiritualism for candid bio

by Morley Walker

No surprise, but Bruce Cockburn's thick new memoir is much like the man himself -- thoughtful, earnest and self-aware.

He is not above tooting his own horn, though he tends to do this by quoting his respectful reviews. Like the prototypical Canadian he is, the folk-rock singer-songwriter's default position appears to be self-abasement.

On his first marriage, to the mother of his first daughter:

"In large part our marriage broke down because I could not open up," he writes. "I remained mired in my childhood psyche, unable to adequately express feelings, to demonstrate or even appreciate the love that simmered in my soul."

Indeed, a major theme in Rumours of Glory is Cockburn's lifelong quest to overcome the "flatlining of emotional content that was the unstated rule in my childhood home."

The other, of course, is his need to understand and express what he calls, over and over in these pages, his "relationship with the Divine."

Cockburn, 69, has enjoyed a great run in Canadian popular music. He has released 31 albums of original material since 1970, including such much-covered songs as If I Had a Rocket Launcher, Where the Lions Are and Lovers in a Dangerous Time. His mantel overflows with Juno Awards. He has won a Governor General's Performing Arts Award and has been made an officer in the Order of Canada.

Creatively and productively, he belongs in the pantheon with Gordon Lightfoot, Neil Young and Leonard Cohen. Yet, like the Tragically Hip, say, he has never quite succeeded abroad.

Maybe he is just too darned Canadian.

Raised in a comfortable middle-class home in Ottawa, the eldest of three sons, Cockburn relates his life story in chronological fashion. For someone who went on to consume a library of books, he was a dud at academics, barely passing high school and lasting less than a year at Boston's Berklee College of Music.

He did, however, land in Toronto at the right time, in 1967, just as the post-Dylan era of troubadours exploded. He takes his title, by the way, from the well-known song from his 1980 album Humans.

Most popular music biographies focus on the minutiae of recording and touring. Cockburn does this, too, but ventures down many side roads of politics and history.

This is to be expected from a musician who has travelled the world as a social activist, and it gives the book a heft rarely encountered in showbiz memoirs.

Especially impressive are his chapters on Central America, through which he toured regularly in the '80s, often risking life and limb.

Critics have long lauded Cockburn for his guitar playing. But for all his eloquence on the battered shape of his soul, or the social conditions in Pinochet's Chile, he has trouble articulating what separates him from the musical pack.

The best he can do is to describe his playing chops as "a combination of country blues fingerpicking and poorly absorbed jazz training."

He seems to think of himself as more of a word guy. He intersperses the text with the full lyrics of dozens of his songs, illustrating how he distilled them from his personal experiences.

He may be the only male musician to confess to inadequacies between the sheets. "We didn't have much of a sex life," he says about his first wife, Kitty. "I remained too trapped inside myself to be much of a lover."

But he has given his sex life the old college try. A determined serial monogamist, he is now on his fifth or sixth long-term relationship (an exhausted reviewer can lose track), which has produced a second daughter, 35 years younger than his first.

Cockburn has remained much more faithful to his manager, Toronto music mogul Bernie Finkelstein, whom he lauds despite their differing personalities.

He grinds a few axes and gets even with a couple of enemies in the music biz. But as a rule, he is respectful of the many big names with whom he has crossed paths. At one point, he admits to breaking into tears at a restaurant when record producer T Bone Burnett called him a hypocrite.

Cockburn's religiosity may be the only subject that takes up more space here than his feelings of emotional constipation. His parents were garden-variety Protestants, but by his early 20s, he was testing out more fundamentalist waters.

His left-wing political convictions separated him from many of his fellow Christians -- especially U.S. evangelicals -- and over the decades his cosmology has evolved into mystical realms that some might see as indistinguishable from Buddhism or, worse, United Churchdom.

He also has to engage in intellectual gymnastics to square his Christian beliefs with an affair with a married woman he had in Los Angeles in the 1990s. He refers to her as "Madame X," and seems to continue to carry a torch for her.

But to give him credit, Cockburn is unafraid to attempt to express the inexpressible. The one subject he remains mum about is money.

He excuses this by insisting, several times, that art and Mammon inhabit separate temples. But it would be interesting to learn how well he has done financially from his back catalogue and songwriting royalties.

Overall, this is a rewarding read, candid and erudite, even where it is a bit plodding. Does the world need another summary of the events of 9/11?

Nowhere does he acknowledge a ghost writer, so one assumes Cockburn penned every word himself. The book ends in 2004, and one imagines him having spent much of the last decade in his den in San Francisco -- where he resides with his current wife, M.J. Hannett, and their three-year-old daughter -- methodically chipping away at the granite block of his life story.

Rumours of glory? Neither premature nor undeserved.

November 7, 2014

Maclean's

Sex, guns and Bruce Cockburn: book review

by Michael Barclay

One of the advantages of age is being able to laugh at your own youth –which Cockburn does in his new memoir.

Rumours of Glory - Bruce Cockburn

Sex, guns and God—probably not what you expect from a Bruce Cockburn autobiography. Well, maybe the God part, if you were a fan of the Canadian musician’s work during the mid-’70s, his most explicitly Christian period. You might not know about his love of firearms or his erotically charged—okay, perfectly normal string of failed relationships, which he writes about candidly. You might, however, be surprised this book even exists, considering Cockburn’s ambivalence about his own fame. When his first album came out in 1970, he heard it played in its entirety on CHUM-FM as he walked around Toronto’s hippie enclave, Yorkville. “Most performers would have been thrilled. I was terrified. I thought, ‘I’m never going to have privacy again!’ ” Yet, here he is, 44 years later, with a memoir about, as he puts it, “making music, making love, making mistakes, making my way across this beautiful and dangerous planet.”

A surprisingly large portion of his book portrays a man who came to Christianity as an adult, after dabbling in the occult, and whose ever-evolving understanding of faith and the Divine manifests itself in every aspect of his life and art. He is a searcher; his songs are often reportage of his travels, philosophical and physical. But there is also some juice here. His first album was funded by a shady drug dealer. At a concert in Italy, armed men suddenly started moving around his equipment, mid-song; there had been an anarchist bomb threat.

It’s hard to imagine a more Canadian memoir: a serious, self-righteous, self-deprecating and quietly talented artist who purposely avoided pursuing success outside Canada until he landed a Top 40 hit in 1979, Wondering Where the Lions Are. (That gave his U.S. record-label head a few strange promotional ideas—including “showing up at a radio station with a lion on a leash, scaring the s–t out of everybody.”) Cockburn’s marriage fell apart because, he says, he was “unable to adequately express feeling.” That would probably do it, yeah.

If you’ve ever heard a Bruce Cockburn song, you know he’s earnest—often to a fault. Here’s a guy who admits, when writing about his not-so-wild youth: “In my mind, life was too serious and weighty to actually be ‘fun.’ This outlook set in toward my teens and didn’t dissipate for the next 30 years.” When did that change, exactly? He doesn’t say. But one of the advantages of age is being able to laugh at your own youth—which Cockburn does. Earnestly, of course.

November 3, 2014

November 3, 2014

The Edmonton Journal

Bruce Cockburn shares stories behind his lyrics in new memoir

by By Sandra Sperounes

EDMONTON - Bruce Cockburn has always had a way with words.

Over his five-decade, 31-album career, he’s demonstrated his prowess as a songwriter, giving us memorable lyrics about love, landscape and socio-political injustice. Even Bono, the world’s biggest rock star, used a variation of some of Cockburn’s lines from Lovers in a Dangerous Time — “Got to kick at the darkness ‘till it bleeds daylight” — in one of U2’s tunes.

The Ottawa-bred musician, 69, almost always writes his lyrics first. “I don’t know why it started like that but I find it easier to manipulate music than words,” he reflects during a recent interview at an Edmonton hotel. (He was in town for the Blue Dot Tour at the Winspear with David Suzuki.) He almost always writes about his own experiences, too — whether it’s a recurring dream of lions, a trip to Nepal, or the desire to blow someone away with a rocket launcher.

And so, it makes sense for Cockburn’s memoir, Rumours of Glory, due Tuesday on HarperCollins, to feature the lyrics to dozens of songs — and the stories behind them. (A nine-disc companion boxset is also available via his label, True North.) Those stories encapsulate his faith, his travels across Canada, his work as a human-rights activist — visiting victims of war in Central America, Mozambique, Chile, Cambodia, Vietnam, Iraq — and his emotional evolution as a man.

“HarperCollins came to me to do what they called a spiritual memoir, which they couldn’t define,” recalls Cockburn.

“I had no idea. So much of my growth, spiritually and personally, has been tied up in my relationships and my intimate relationships with women. I asked my editor at one point, ‘How Henry Miller can I get with this?’ He said, ‘We can handle that.’ In the end, it’s not like that at all.”

Unlike Miller’s spiritual and sexually graphic works, Rumours of Glory is as tame as a house cat. The memoir, co-written by journalist Greg King, documents Cockburn’s childhood in Ottawa, his rise as one of Canada’s top singer-songwriters/political activists, his struggles with Christianity, and a few modest tales about the women in his life.

Revelations include:

* “I was like a chainsaw rendering of Rodin’s The Thinker done in ice, a frozen simulacrum of anger, avoidance, and angst in the posture of a man taking a dump,” he writes, referring to his shortcomings as a husband to his first wife, Kitty, in the 1970s.

* He had a brief affair with a married woman, only identified as Madame X.

* He’s legally blind in his left eye, the result of a fungal infection passed on by bird droppings.

* He works with a dream specialist, as an attempt to get closer to what he calls “the Divine.”

* He once passed up the chance to jam with legendary singer/guitarist Jimi Hendrix.

Cockburn is also regarded as a gifted guitarist. Nowadays, he suffers from arthritis in both hands, what he refers to as “wear and tear,” which he usually treats with fermented grapes. You won’t find any mention of this, however, in Rumours of Glory.

“Medications don’t work as well as wine for loosening up the fingers and making them not hurt so much,” he smiles. “I can play most of what I used to be able to do — it hasn’t interfered with playing that much.”

His memoir is also short on details about his life in San Francisco, where he now lives with his wife, M.J. Hannett, an immigration lawyer for Homeland Security, and their almost three-year-old daughter, Iona. “That’s volume two, I guess,” he says.

Iona is Cockburn’s second daughter. His first, Jenny, is in her late 30s, teaches at Concordia University in Montreal, and has four children of her own.

“It’s pretty different,” he says of his current approach to fatherhood. “I mean, the mechanics of it are the same, from the starting point onward. But my attitude is much more relaxed than it was. When I was younger, I just worried about more stuff. There was much more of a need to keep focused on writing and playing and practising. I took it all very seriously, and I still do, but I’m just not as worried about it.”

While he worries about his mortality — “I hope I’m around long enough to see (Iona) get on a good footing” — he’s also concerned about the state of our world, currently ravaged by disease, environmental disasters, religious extremism and war.

“Things are really chaotic right now. It feels like entropy, it feels like the whole world is spinning out of control.”

How do we make it stop?

“How do we make the world a better place? By respecting each other. If you can’t imagine loving your neighbour, at least respect them and require them to respect you. When we don’t do that is when we cause all kinds of trouble for ourselves and everybody else.”

© Copyright (c) The Edmonton Journal

Photo: Ed Kaiser

October 30, 2014

The Boston Globe

Cockburn Celebrates with Memoir, Box Set

by Sarah Rodman

Revered Canadian singer-songwriter-guitarist Bruce Cockburn hasn’t released an album since 2011, but he’s making up for the gap in a big way. This week he released an engrossing memoir called “Rumours of Glory,” detailing his 40-plus-year artistic career and how it intersected with his spiritual awakenings and activism. Next week, he will unleash a nine-CD box set of the same name that serves as a companion to the book.

Cockburn comes to the Somerville Theatre Saturday — a few tickets remained at press time. The concert will celebrate a career that has seen Cockburn combining folk, jazz, pop, and rock in hits like “If I Had a Rocket Launcher,” “Wondering Where the Lions Are,” and “Lovers in a Dangerous Time,” even as his humanitarian and social-justice efforts have taken him to the far corners of the globe.

We caught up with the amiable Cockburn, 69, by phone from San Francisco recently to chat about his life’s work, and wondered aloud whether we should read anything into all of this activity, as well as the 2013 release of the career-spanning documentary “Pacing the Cage.”

“I’m not retiring anytime soon,” he replied with a chuckle.

Q. Why was now the time to write “Rumours of Glory”?

A.Harper Collins came along with an offer. [Laughs.] It was not the first time that someone had had the idea. They approached me about doing a spiritual memoir, but they couldn’t quite tell me what they meant by that. But it sounded like an interesting approach to the memoir thing, and appropriate to me.

Q. Were you concurrently curating the box set?

A.The box set came after. Basically what the box set consists of is all the songs mentioned in the book, in the order in which they’re mentioned, and a bonus CD of previously unreleased or rarely released material. There’s also a concert DVD in there. It’s a slightly odd premise for a box set, I think, but interesting, and it ties in well with the book. I think people who are interested in the music because of reading the book will have that reference and entry point into the music. And the people who already know the music maybe don’t have all of that stuff.

Q. There is a perception, given the nature of your music and activist pursuits, that you are a very serious person, so it was nice to see your humor come though in the book . . .

A. That’s good!

Q. . . . and many of the parts that are laugh-out-loud funny — your initial reaction of horror at people actually dancing at your shows for one — are when you seem to be poking fun at your own emotional remoteness, which seems awfully enlightened of you.

A.I’m glad you take it that way. I suppose it could be viewed as narcissism, too. The mandate was to do a spiritual memoir, and you can’t talk about spirituality without talking about your personal life and your personal experiences and inner experiences, so it really seemed necessary to go to those places.

Q. There is a chapter early on detailing your time in Boston in the mid-’60s when you attended Berklee. It certainly sounds like it was a formative experience, seeing legendary folk and jazz artists at Club 47 and the Jazz Workshop.

A. Oh yeah. It was surreal actually when I look back at it. [There are] things that didn’t make it into the book, but when I think back about being in Boston, when I arrived at Berklee I was the only guy in the school with long hair. It was 1964, and the Beatles weren’t new by that time, but I had hair that was longer than the Beatle haircut. The heroin dealers would always approach me instead of the other guys because they thought I looked the part. [Laughs.] Every now and then a carload of young people from the suburbs would pull up alongside me and yell out things like “Hey Ringo!” or “Are you a boy or are you a girl?” I could have done a whole book just on being in Boston and the surreal quality it had, which was partly a product of the times as well as the time of my own life. As well as the folk people, I heard so much incredible jazz. The atmosphere just walking down alleys and hearing music coming out of everywhere around the school — there were always people practicing or jamming. And it was a great atmosphere from that point of view, far more instructive to me than the school was, because of my own particular inabilities to get down and study hard.

Q. Or be on time?

A. Yeah, that. [Laughs.]

Q. Reading the stories behind the songs and different facets of your career, there seems to have been at no point any fear associated with expressing your political or spiritual beliefs either in song or in life, even though those can be touchy subjects for popular artists.

A. No. I never had any fear associated with [the religious or spiritual aspects]. There was the mild sense of, “Well, maybe some people are not going to like this and they’re going to stop buying my records.” That was obvious, and it sort of happened, but then they were replaced by other people who were newly interested, so it didn’t really change the numbers. I was aware of that and sensitive to it, but afraid? No. With the political stuff, you’re liable to get an angrier kind of backlash, and occasionally there’s been issues where I’ve thought, “I wonder if somebody’s going to show up and do something unpredictable or mean.” [Laughs.] But it hasn’t happened, so the more you do and the more that’s the result, the more confident you are about going out and doing what there is to do.

Q. Does it disappoint you that more artists don’t engage in social commentary in their music?

A. It does a little, but it’s not for me to tell other people what to do. I think it’s disappointing that more people just don’t go out there and be genuine. But having said that, an awful lot of people do do that. [Laughs.] I feel like what I do is extend an invitation: This is what I saw, this is what I felt, if you’d been there, you probably would have felt similarly, take a look. That’s as close as I hope to get to proselytizing: It’s something I don’t really want to do, but I do feel like laying it out for people is worthwhile. And if people then feel motivated to dig deeper, then great.

Interview was condensed and edited.

September 2014, Wininpeg: Bruce autographing the Rumours of Glory box set.