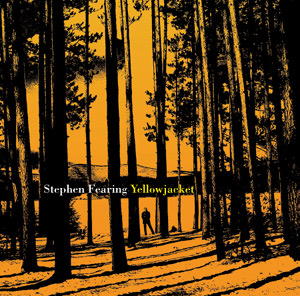

Yellowjacket

TND 410

Released April 11, 2006

Produced by Stephen Fearing

Engineered by Scott Merritt at The Cottage in Guelph, Ontario

Players include: Dan Whiteley, Colin Linden, Suzie Vinnick, Jeff Bird, Richard Bell, John Dymond, Gary Craig, David Travers Smith, Paul Earle, Ellen Moore, Elspeth Thomson, Tom Mueller, Josh Finlayson, Scott Merritt, Michael Dragoman

1. Yellowjacket 2. The Man Who Married Music 3. One Flat Tire 4. Love Only Knows 5. Like Every Other Morning 6. When My Work Is Done 7. Whoville 8. This Guitar 9. Johnny’s Lament 10. Ball ‘n’ Chain 11. Goodnight Moon

Interview with Stephen Fearing from his home in Ontario on April 14, 2006

by Daniel Keebler

DK: How did you get started with True North Records?

It goes back to when I was recording the album, Blue Line, in England. I was working with a agent/manager named John Martin… no relation to the singer, John Martyn. In Canada I was working with a woman named Joyce Hinton who was working really hard on my behalf getting shows. Things were just starting for me. We were trying to figure out what a manager’s job was exactly. I came back to Canada with this new record… I had recorded it in England. It precipitated a whole bunch of things. I realized I needed someone to manage me who was doing more than what she was doing. She was working as an agent. I was just starting to understand the difference. We tried to make that work but our relationship ended. I found myself with a record and no management in Canada and my management in England was more like a friend helping me out. In England, where the album had originally come out on Rough Trade Records, Rough Trade went belly-up right about the time the record was released. So, there I was with no label and no manager and this brand new record. It was all looking a bit rough. I had been looking for a label in Canada and Joyce had gotten me in touch with a lawyer named Graham Henderson --- we had been looking for a label in Canada before the whole thing went south with Rough Trade. Graham and I were discussing various labels and options. I phoned him up and said that I was looking for a manager as well, as Joyce and I were no longer working together. He said he knew exactly what to do. He explained to me that Bernie was very interested in both the record and in managing me, but because he’s a gentleman he’d been basically standing back. He didn’t just want to take the record, he wanted to manage me as well, but he didn’t want to put me in a conflict by coming on as the big high-powered Toronto manager and forcing me to make a decision. But, since the decision had already been made he stepped forward and said he wanted to manage me. At that point he came and saw me play a show at the Banff Centre and a show in Toronto with Willie P. Bennett and Eric Anderson. It was a triple bill… Bernie came to that. There was some press written up about the fact that Bernie was checking me out. He basically made me an offer and away we went. I thought he did it in a very lovely way.

DK: Is Yellowjacket your seventh solo album?

It’s my seventh formally released record in terms of the general public being concerned, but it’s actually my eighth because I did put out a thing called The Yellow Tape that was my first solo effort. I put it out myself… sitting at the kitchen table with J-cards and sticking on labels and basically making about twenty cassettes at a time and taking them to the gig. That was officially my first release. Coincidentally, and this was pointed out to me by a guy who interviewed me recently, Yellow Tape was released twenty years ago and Yellowjacket has come out exactly twenty years after and The Yellow Tape was self-produced and Yellowjacket was self-produced. There’s a whole bunch of things, including the “yellow” in the title… it’s just one of those weird coincidence things, but kind of interesting, too.

DK: What has become of The Yellow Tape? I assume it’s not out there for purchase.

No, it’s not. If I made a thousand I’d be surprised, but I have a couple of copies. Recently I was going through old cardboard boxes of files and junk and I came upon a little stack of the J-cards, which was kind of neat. A friend/fan of mine, who put together the first website for me, he digitized it… he put it onto a CD. Bernie and I have sort of talked about perhaps we’d release it someday. It’s pretty rough.

DK: Other than The Yellow Tape, this is your first outing at producing one of your own records. How did that go related to how you thought it might go?

It went well. I think the thing that surprised me the most, and I wasn’t prepared for and it kind of blind-sided me a little bit, was when we started to do the mixing I just really questioned everything. I think everybody goes through that. I definitely go through this cycle with making records where the highs are pretty high and the lows are pretty low. Then there’s a point at the end where you think it’s all done, I can’t change anything. It’s usually during the mixing that you realize this is what the record is gonna sound like. You start to hear it as a whole as opposed to a bunch of individual pieces. I always go through this period of incredible doubt. This time it was even stronger. What I’m really noticing, and Bernie and I were talking about this the other day when we had lunch, is that there is just a feeling that I want to know what True North is doing… I want to know every single thing they’re doing about this record. I want to know what ads they’ve taken out. I think it’s partly because I’m not playing a whole bunch of shows right now -- I’m waiting for the record to come out and then taking off for England – and also because I produced it. These were Bernie’s words, and I think he’s right: “When you produce a record you make more of a statement than if you just write the songs and play them.” It’s like a third element of putting your stamp on it. You kind of chew your nails more. That surprised me. I’m really happy with the actual production of it. I picked the right studio to do it in and I picked the right guy to do it with. Scott Merritt is a lovely, gentle, calm, grounded kind of guy. He’s much slower than me. I was always pushing him and he was always pulling me to slow down a little bit.

DK: What was Scott’s role?

He was the engineer. I didn’t want a producer; I wanted it to be me and an engineer. That means that I produced it, but I really thought of it as a collaboration in a lot of ways. It was his choice of mic placement and mics, and that’s such a huge part of the record. I listened to and went “That sounds great.” If I hadn’t liked it I would have said “We gotta change that,” but he initially made these macro decisions that were really important. I produced it… I went and did the paperwork and did my arrangements and all that, but the sounds of the record is so much a part… it’s him. He came up with that. His role was to make sure we got it on tape… he was my safety net. He stayed out my way until he saw me coming close to the edge of the cliff and then he would say “You might not want to do that because…” He’s quite happy to stay out of the way but he’s also willing to speak up.

DK: There are a few songs that were co-written.

There are four songs that I co-wrote with a fellow named Josh Finlayson who is in a band called The Skydiggers. A venerable Toronto band that’s been around a long time. Tom [Wilson] and I initially started the tune Yellowjacket together… he didn’t have that much to do with it. He and I batted the idea around for awhile and then he signed off on it and said, “I’ve got nothing more to add. I think this is your song.”

DK: When I listen to a song like The Man Who Married Music, I’m assuming there is some personal connection there.

For sure. You can look at the two poles of purely autobiographical and complete fiction. The songs vacillate in degrees between those to poles. A song like The Man Who Married Music is very autobiographical. The context behind it was interesting. My daughter was having a baby and I was in Ireland… this was last spring. I was staying in my parent’s house in my childhood bedroom, with the old posters on the wall and the whole deal… sleeping in a little single bed. It was a very strange feeling but kinda cool. I had a dream that my wife was pregnant, because babies and pregnancy was pretty much on my mind. We were planning that Rebecca, our daughter, would be holding off from having the baby until we got back from this trip but there was a little bit of consternation about that, and my wife, Chris, was worried. So, it was very much on my mind. So, I wake up in the middle of the night, having had this dream that Chris was pregnant and that was a pretty freaky thought. I initially woke up with my heart beating quickly. Then immediately grabbed my pen and paper and started writing this dream down. Then you take a step back and look at yourself and go “What a mercenary you are!” [laughter] You can’t just have a dream like everybody else. You’ve got to write it down with the view of writing a song a bout it. At that point I start looking at the whole process as a kind of self-analysis that I think songwriters go through. The only way that you can do this job with any kind of longevity is if you are willing to… and I think all writers go through this… I don’t know if painters do… but I think that all writers go through this thing of you get an idea, you write it down right away. Everything is grist for the mill. A dream like that is just “Oh, Boy. Quick, get the paper.”

Colin [Linden] and I talk about how he’ll wake up in the night with a melody and he’ll get out of bed, go in the other room and put it on tape. In the morning he’ll go back and listen to it… it’s basically dreaming songs. It doesn’t happen to me that often, but when I do get an idea I’m smart enough now to write them down. When it’s something as intimate as your wife having a baby you think “Jesus, is nothing sacred!?” [laughter]

A song like One Flat Tire goes back-and-forth. There’s some fiction in it. I passed a guy on the side of the road changing his tire on a horrible, rainy night. It wasn’t me, but it’s much more interesting if I put myself in his shoes. You start using the metaphor of having a flat tire and it becomes much more personal. Talking about Bernie going to hospital… that’s our Bernie.

When I co-write a song it’s a very interesting mix of putting yourself in the other person’s shoes and trying to get them to wear yours, or both of you completely concocting something that hasn’t necessarily happened directly to you, but you have some feel for. It’s neat because you can use the other person’s experience to help you authenticate a song if you haven’t experienced it yourself.

There’s a fundamental difference with this record from all the other recording I’ve done before, and that’s that a lot of these songs started life as a melody, not the other way around. I traditionally have written with a notebook and a lyric idea and then when I have enough lyric I start putting a melody to it. I usually have to hold the melody back because it’s a little like quick-drying cement… once you attach the two together it’s very hard to separate them. If you hit a brick wall you’re kind of committed to a form. It’s just one way of writing, and perhaps a more intellectual way of writing. What I’ve found is that I have these melodies that pop into my head all the time. I whistle then and I forget about them, I don’t pay much attention to them. With this album I thought, “You know, I should really pay attention to those melodies,” so I spent quite a bit of time out here in my shed with my little laptop and my guitar la-la-la-ing along. Just creating melodies and coming up with whole songs that have no lyrics to them. That’s very intimidating. It’s like the difference between writing an essay about how you spent your summer vacation or writing an essay about anything you want. Some people find one or the other harder. It’s hard to write lyric into a form. I was coming up with these melodies that I really, really loved, but they had a specific structure to them, they had a really specific line to them and I didn’t want to change that. A couple of times I threw myself at them with the intent of writing lyric… it felt like it was not going anywhere. That was when I called my friend Josh Finlayson. I said “I need you to help me with some of these songs.” Two of them, Love Only Knows and This Guitar, were ones that I had a very strong melody and chord pattern for but no lyric. So, I gave them to him and he goes away, comes back the next day and says, “Well, I got this idea for the first line of the chorus… ‘Love only knows.’” It fits the actual meter of “Love only knows what happens now…” It fits quite beautifully with the melody. It’s like he comes up with the springboard and then the two of you dive in together.

I firmly believe now that the process really affects the songs. You start with something that comes instinctively from your gut… and melody is so instinctive. Then you let that be the king and you try to figure out what it’s trying to say and write lyric that will somehow capture that feeling. It’s a really different way of doing it. He came up with that great first line. If I’d come up with that line on my own I would have rejected it because I would have felt like it was corny. But because he brought it I looked at it and went “Of course it has to be about that. It has to be a love song. There’s no way this melody can be about anything else.” Both of us were writing it from the perspective of watching their child grow up and leave. I don’t really have that experience because I’m a stepfather. I had to wear his shoes.

There’s a lightness to this record… even though the tempos are kind of slow on a lot of them there’s something lighter about this whole record. I think a lot of that is how the songs were written.

DK: Goodnight Moon is a bit of a departure for you vocally. Where did you find that song?

It came from a magazine called The Oxford American. This one issue they do every year is just music and they give you a CD sampler with it. There will be an essay on every song and the artist who is singing it and why it’s important and how they fit in with the whole scheme of things. It’s all southern culture. One of the last tracks on this sampler was Will Kimbrough’s song, Goodnight Moon. It just knocked me out. It’s too far from his version. I wanted to change it. I wanted to sing it in a different key. I changed some of the chords a little bit… I made some of the chords a little bit more dense, but I ended up singing it in the same key. It forces me to sing… because there’s a real range in that song, in terms of from low notes to high. You have to break into a falsetto at some point… it’s just where do you want to break? He sings it in the key of G. I tried singing it in A. I tried singing it in B. I sang under him, I sang over him. Ultimately I realized he was singing it in the best key for a male voice, so that you break into your falsetto at a certain point and it really works with the line.

The way we recorded that was that we tried not to be too precious. So, every day I’d come into the studio and we’d have microphones set up and I’d just grab my guitar and sing it two or three times. Then we’d forget it, and go on to the next thing and work on that. The next day we’d have another go at it. Similarly, with the instrumental, Whoville, we did the same thing… we just had a go at it every day until we felt like we got it. With Goodnight Moon I was really struggling, because as I say, I was trying to make it different from Will Kimbrough’s version. I came in one day and Scott had hooked up my little Hammertone, which is a wonderful little guitar. It’s a twelve-string electric guitar that’s in the mandolin range. It’s a tiny guitar with a short neck and a solid body. He’d plugged it into… he has a Hammond B3 and a Leslie rotating speaker… he’d plugged it directly into the Leslie speaker and it was just the most gorgeous sound. Immediately I went “That’s it. That’s the sound that I’m going to use.” We recorded two versions of it. I started singing and he rolled tape, and when I finished the song I was just noodling around and went right into the second version. We did a bunch of messing around with delays and we got Richard Bell to play a little bit of Wurlitzer on it and I put in another electric guitar part. It now actually fairly different from Will Kimbrough’s because he recorded it with a band… with bass and drums. I wanted to make mine as whole lot more dreamy. The fact that I’m a grandfather and the fact that I have a little grand daughter, who very soon will be reading that little kids book called Goodnight Moon, that definitely had a part to play in it, too. The song captures so many things that are in my record: the image of the car broken down, the going away, the saying goodbye. The fact there is the element of kids in it… it just really caught a whole lot of things. So it was perfect.

DK: Is there something that you are most proud of in the work you have done over these past eight albums?

I guess I really haven’t thought about it that much and I’m probably not going to think about it in that way. I feel very much like I’m looking ahead because I feel like I’ve just discovered a new way to write songs, which is really exciting to me. I don’t know if I’m more paranoid or neurotic than the next songwriter but I think I’m right up there… in that I finish a song and I think “Wow, what am I gonna write about now?” They’re like little mini novels. So you finish and you think, “What am I going to do now?” I’ve got to write another eight songs for this record. It’s a bit terrifying, so to realize that at the start of my eighth album I figure out a new way to write songs is really exciting. The other thing that’s different with this record that is also inspiring to me is the electric guitar. At the tender age of 43 and eight albums into my career, I’m actually thinking of myself as an electric guitar player now. I was dabbling before, but Blackie and The Rodeo Kings has really allowed me the opportunity to kinda go to school. I’m playing with what I consider one of the best electric-roots slide players in the world. I get to play right beside him and I get to pick his brain and watch him. That’s starting to reflect in my own playing.

The thing I’m most interested in doing, and I think I talked with you about this the last time I was at your house, is this singer/songwriter thing is not very interesting to me anymore. But, being a songwriter is really exciting to me. In fact, I can’t tell you how excited I am about that. There’s something fundamentally different for me between being a songwriter and being a singer/songwriter. I love performing so it’s not that I want to lose that aspect of it, but there’s something about the singer/songwriter genre that’s sort of a dead end for me. When I listen to some of my peers I find it boring and I don’t see them evolving and discovering new things. I feel like there’s a craft there that I’m just starting to tackle and it’s very exiting to me. I guess in some ways in looking forward I’m really looking backward, because a lot of these forms are really very old. I’m starting to look back at artists like Charlie Rich, some of the artists that ten years ago I wouldn’t have really been interested in at all. I’m looking at them again and re-evaluating what I think they do and why I should actually listen to them and pay attention now. I’m a slow developer, man. I take a lot of inspiration from artists like Lucinda Williams who is in her 50s and she’s just getting better and better, as opposed to that ethos of “you do your best work when you're twenty, then better to burn out than rust.” I think there’s something great about watching artists… and Bruce is a good example, too, of people who just keep following their muse, and in so doing they discover new things and they come up with new ways to say whatever the themes of their life are. They figure out how to do it again and again and again. Bernie played me a couple of cuts off his new record and it’s really astounding. He’s doing stuff that I haven’t really heard him do before as well. He’s using his falsetto a lot more. Working with Jon Goldsmith again he’s… it’s like he’s making a record with someone who clearly has done a lot of film scoring so there’s a size and sound to the record that I haven’t heard on his records before. He’s re-inventing himself and that’s very inspirational to me.

DK: In recently listening to all of your CDs in sequence I feel that your work has grown to a good place with Yellowjacket. It must be exciting to think that a new door has opened for you.

Yes, it’s really exciting. I’ve been very lucky. I’ve had people who have championed my stuff from pretty early on. I appreciate the fact that they did… there’s a great freedom in that. Certainly being able to work with a label like True North has given me a really great freedom. I actually think I’m doing the best I’ve done right now. The only thing that’s a drag about that is that it’s impossible to get the same kind of attention and focus from newspapers, from whomever, as you do when you initially come out of the box. In some ways it’s too bad. It’s early days with for me with this record yet. I don’t know if people are gonna hear it the way I hope they will and the way I wish they would. I suspect that people are going to listen to it and go “Oh, Stephen Fearing, we like him and he crafts a good song…” I don’t know if they’re gonna hear that there’s a fundamental change that’s happened. That’s what I feel. I just hope that some of the people who have been listening to my stuff for awhile will hear that. I sometimes think that maybe if you come to me for the first time and listen to my work and go backwards you think, “Yeah, there is this growth.”

DK: Why did you produce this album yourself?

I really felt like it was time. There’s a couple of practical reasons, too… budget. [laughter] If I’m going to hire a producer I’m not going to want to go backwards, in terms of I got to work with Colin, and he’s an amazing producer. You can ask favors from your friends for awhile then you gotta come up with the dough. I knew there wasn’t going to be a big budget for this record so that was one of the reasons, certainly not the main reason but definitely one of them. Another reason would be that I feel confident in saying, at this point, that I think this whole thing with the Rodeo Kings is something I’m going to be doing hopefully for as long as I/we want to. I would be really surprised if in twenty years we aren’t still doing it. So I’m going to get to work with Colin from here on out. I thought maybe it’s time to work with somebody else. I thought, “Who am I going to get to work with?” I don’t really want to start a new relationship with somebody just now, so I thought maybe I’d just do it myself. I’ve learned a lot…. I’ve gotten to work very closely with Colin. We co-produced the last one, which meant that I was much more involved with it.

I’ve spent a lot of time doing this solo thing and it’s something I’m proud of and I really enjoy. I want to keep it going and keep it developing. I would never want to let go of it. END

Ed. Note: I think Yellowjacket is the best work to date from Mr. Fearing. It really is different from all previous works. I do hope this is the start of something new for a fine songwriter and a pretty friendly guy.

Stephen will be touring the U.K. in April and May, 2006. stephenfearing.com

"And they call me Yellowjacket

'Cause I never run away"

Ed. Note II: Stephen won his first Juno as a solo artist as the winner in the Roots and Traditional Album of the Year - Solo category in April, 2007, for Yellowjacket.

Yellowjacket Review

Artist: Stephen Fearing

Title: Yellowjacket

Label: True North CD: TND 410

Recorded by Scott Merritt

Produced by Stephen Fearing

Released: 11th April 2006

Running Time: 43.53 minutes

Review by Richard Hoare

After half a dozen albums Stephen Fearing has come of age. This is a complete, mature and eclectic record of songs with no fillers. Stephen started with the music, using his own unused melodies combined with classic song writing figures from previous decades to come up with fresh and potent songs. He has raised his game and gone up a level to produce a work that I would compare with the adult nature of Lucinda Williams recent albums. Stephen has included some co- written material including four with Josh Finlayson, from the Canadian band, Skydiggers, who also provides harmonies on one track. Where there is a rhythm section Gary Craig, often employed in recent years by Cockburn, is seated at the drums coupled with bass players Jeff Bird or John Dymond.

To gain control of the project, Fearing stepped into the role of producer for the first time and employed Scott Merritt as engineer. Scott, his photograph is on the credits page of the CD booklet, was the midwife of this project providing the studio and engineering skills. Merritt’s studio, The Cottage is located in Guelph, Ontario. Stephen lives in the same town so he could cycle to work! Merritt was well placed to assist Fearing as he has several albums of his own under his belt as well a number of production credits. In 1979 a then unknown Daniel Lanois recorded Scott’s own first album, Desperate Cowboys. Merritt has particular skill in the choice and placement of microphones.

1. Yellowjacket

The song title entwines the dual identity of the word for a North American wasp and a proprietary trucker’s capsule for staying awake on the road, a potent over the counter legal energiser. Stephen’s signature guitar segues into the big swelling sound of powerful strings and back again. When I asked Stephen whether the term Big Beat was a reference to the 1966 Donald Myrus book Ballads, Blues and The Big Beat he referred me to The Doors song The Wasp (Texas Radio and The Big Beat) from their 1971 tour de force album LA Woman. Fearing started to write this song with Tom Wilson, one third of Blackie & the Rodeo Kings. Tom also has his own album, Dog Years, out on True North, released earlier this year.

2. The Man Who Married Music

This is performed by an acoustic trio producing wonderful interplay between Stephen’s guitar, the mandolin of Dan Whiteley and Dobro from Colin Linden, the third member of Blackie and The Rodeo Kings. The subject matter is a jigsaw of Stephen’s stepdaughter expecting a baby mixed with Fearing’s perception that it is in fact his wife who is pregnant coupled with Stephen’s yearning for his wife while out on the road.

3. One Flat Tire

A driving rhythm propels this track, another road song, this time based on the passing blowouts on the highways. This is the most instant song on the album before the others flower into your consciousness. The reference to Bernie is Bernie Finkelstein, his manager, who was in hospital in recent times but pulled through. There is a precedent here, in 1979, Cockburn mentioned Bernie in his song How I Spent My Fall Vacation.

4. Love Only Knows

At gigs Fearing announces this song as being about Finlayson’s 14 year old daughter cutting the apron strings with a machete! The opening line “You, you’ve got the eyes of a heart that’s on fire” is perfectly illustrated in the CD booklet by a Halloween pumpkin face flaring by candlelight! The horns arranged by David Travers- Smith convey the exact exquisite emotion and Colin Linden plays a beautiful Dobro, which sounds just like David Lindley.

5. Like Every Other Morning

The subject matter is seemingly a song about departing offspring set in part to a rhythm Cockburn used in 1999 for Last Night Of The World. Fearing also used the same riff for his live rendition of his The Bells of Morning from his 2000 True North album, Blue Line. There are beautiful chiming strings arranged by Michael Dragoman, electric guitar played by Stephen and the harmony vocals of Suzie Vennick. The whole production brings to mind classic popular songs.

6. When My Work Is Done

This song about parents has a great down home bluegrass sound in the style of say, The Soggy Bottom Boys from the film, O Brother, Where Art Thou? It’s the same trio as on The Man Who Married Music but with the drum and percussion of Gary Craig.

7. Whoville

Stephen has written this splendid original acoustic guitar instrumental and named it after the town in the book, How The Grinch Stole Christmas! by Theodor Seuss Geisel. As Fearing puts it “This tune is Dr. Seuss meets John Philip Sousa.” I hear variations on Scott Joplin from compositions like Heliotrope Bouquet.

8. This Guitar

The trio of Fearing, Bird and Craig play while Stephen sings about how he and his sisters sang in the back of the family car when growing up in Ireland.

9. Johnny’s Lament

A Johnny Cash DVD with the on screen quote “Sometimes at night when I hear the wind I wish I was crazy again” was the inspiration for this song. Fearing has huge admiration for Cash and really pulled out the stops with some marvellous vocals and an engaging and sedate pace for the song. The languid guitar, bass and strings produce a beautiful ballad shuffle. Fearing lays awake waiting for the morning sensing “A watercolour morning bringing roses for the dawn.”

10. Ball “n” Chain

Another co-write with Josh Finalyson and a duet performance with Fearing and Richard Bell (Full Tilt Boogie Band, The Band etc) on rolling barrelhouse piano. This song is a paean to the difficulty of personal relationships.

11. Goodnight Moon

Stephen heard this song written and performed by Will Kimbrough on one of those CDs free with a magazine. Fearing was having trouble making it his own until Scott wired his little 12 string Hammertone guitar through a rotating Leslie cabinet to come up with the glowing notes that now decorate the song. Kimbrough may have taken the title of the song from a children’s book of the same name comprising a short poem of goodnight wishes. Stephen excels with a falsetto vocal and the guitar and piano meander to an atmospheric coda.

To top this off Stephen has spent considerable time and attention to detail with Michael Wrycraft to produce a fascinating CD package. The artwork subject matter is a combination of material from Merritt’s house like the “hop” graphic on the back of the booklet and the right arm impression while other items are from Stephen such as the rubber Fearing death mask used in a Blackie and The Rodeo Kings video, the innards of a photographic projector that Stephen uses as an amplifier and a Tom Wilson painting – the face. The glass valve decorated with the cartoon trumpet player is borrowed from a specialist who repairs tube microphones and the children walking hand in hand is a silhouette Stephen picked up Austria. A yellow jacket wasp is hiding on the inside cover of the booklet and Stephen is dwarfed by a forest of immense trees on the cover itself.

If you think you know Stephen Fearing and that I’m recommending a singer songwriter just knocking out another album, think again. This is a disc of consummate songs with great arrangements.

May 2006