Watch "Return to Nepal, with Bruce Cockburn," here.

USC Canada has selected Gavin's Woodpile as one of three sources on the internet to help keep folks connected with Bruce's activities in Nepal. Filmmaker, Robert Lang, will travel with Bruce to document the trip. This page will be in development as the project proceeds. Bruce will leave for Nepal on November 8, arrive on November 10 and finish his work for USC on November 24. Kensington Communications will host audio and video from the journey. Additional information can also be found at the USC Canada Nepal page. From my liaison, Faris Ahmed, at USC Canada comes this brief overview:

Bruce Cockburn travels to Humla, 20 years after his first visit to USC Canada’s program in this remote region of Nepal. His journey is mainly about community food sovereignty: How communities in Humla are meeting the challenges of climate change and externally driven agriculture, and making their own solutions work for the community -- all in the context of political conflict. As Bruce witnesses this, and interacts with key individuals in a few communities in Humla who are making this happen (with USC support), his journey will be captured on video by Robert Lang and Guy Clarkson of Kensington Productions. Using a satellite phone journal entries and stories will be sent back to Canada live from Humla, in the form of audio, video and photo files. These will be posted by Kensington’s technical specialist on to YouTube.

This is the expected schedule for postings of Bruce's activities in Nepal:

Week of November 2 First posting - Bruce’s thoughts before he leaves Canada

Week of November 12 Second posting (voice, video) - Bruce’s Nepal journal

November 15 Third posting - from Humla (Langdung or Bargaon)

November 19 Fourth posting - from Humla

November 23 Fifth posting - from Kathmandu

Week of December 3 Sixth posting - reflections on the journey

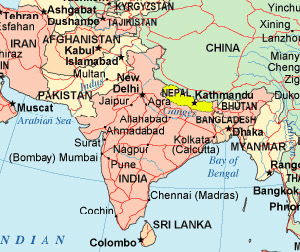

In 2007 Bruce will be heading to Humla, highlighted in red below

October 24, 2007: The following is from a phone interview with USC Director of Canadian Programs, Faris Ahmed.

Faris: What’s on your mind as you plan your journey today?

Bruce: Curiosity, which is always there. I’m curious to see what, if anything, has really changed with the war in the 20 years. I hear that Katmandu has changed a lot. I’ll be curious to see what that is. From my own personal point of view that’s the main motivator, and the chance to go back to a country that’s hands down the most beautiful place on Earth that I’ve seen. That figures rather prominently, too. We’ll be going to a part of Nepal that I didn’t get to before that was officially closed to foreigners in that era. Although I knew people who went there, we couldn’t go there. It will amazing to encounter the culture again. Although we’ll be encountering a slightly different version of it than last time, I think we can expect it to be pretty amazing. It always feels good to me if, in the process of satisfying my curiosity and visiting a beautiful place, I can do something for the people that live there. And I don’t know, one individual doesn’t generally get much done, but another voice added to the chorus can help. As far as motivation goes, that’s what it is.

What do I expect to see? I don’t really know. I’ve seen pictures of Humla and it looks amazing. I have a sense from last time, too, of sights and sounds and smells and the sort of human encounter we are likely to have. I know better than to make too much in the way of assumptions about that because it’s always different – there are themes that run through visits like this. They always have their own character as well.

One of the things that characterizes people living in the difficult conditions that people in Nepal find themselves in – in all parts of the world where those conditions exist – is the superior recognition – I say superior for a reason – superior to us, “civilized” people in this respect. There’s a very well-developed sense of how dependent we humans are on each other, and people in those rural villages in Nepal have that sense. There’s a sense of community that is beyond anything that one encounters in the developed world. I’m not really part of a community myself except in the broadest sense, and I’m not temperamentally inclined to be part of a community particularly, but I see this and I see this is what allows people to survive their difficult circumstances and to support each other physically and emotionally with the amount of hard work and pain that they live with. To put it that way, I don’t mean to ignore the capacity for joy because that’s a thing that’s really evident. I think it’s part of the same phenomenon, that people who are really up against it, and who have been really up against it for a long time… If you’re a family here or anywhere who suddenly comes face-to-face with great difficulty, it’s very hard to be joyful. But if you’re a culture that’s lived with hardship for a long time, the need for, and the capacity for joy will resurface and stay. You find that, like I described with the village of Sarangkot, people were ready to drop everything and start dancing the minute they had an excuse. I’ve seen this in other parts of the world too, and sometimes they’re too sick and too tired to be able to do that but there’s still a sense that, you know, of having a broad sense – how do I put this – just of being aware that life is made up of all the things it’s made up of. Even though from a material point of view they’re deprived of some of those important things, that has not led to them foregoing the parts that are accessible to them and that includes the ability to celebrate. So, you know we’ll see. That looks different in every culture and we’ll see about that in this case. Obviously, it’ll also be interesting to see what the impact of the war has been on that sense of community because that often has a part to play and that means it could go either way. When people are in a war that can fragment a community but it can also cause it to become very strong. I don’t know what to expect in that regard except that these communities are still there and the USC is still working in those communities, it’s just that they’re probably doing okay. -END

NOVEMBER 5, 2007

USC PRESS RELEASE

Witnessing “the Most Beautiful Place on Earth”

Bruce Cockburn returns to Nepal after 20 years

Ottawa, November 5, 2007 - Twenty years after his first visit to Nepal, Canadian singer/songwriter Bruce Cockburn is going back to the country he calls “hands down the most beautiful place on earth that I’ve seen.”

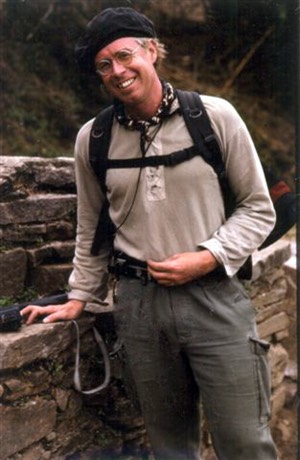

Cockburn returns to Nepal with the same travel companion as on his first trip in 1987 -- Susan Walsh, USC Canada’s Executive Director. They will journey on foot, staying in the villages of Humla district, located in the northwest corner of the country. This remote Himalayan region, close to the Tibet border, gained importance through history as a passage for salt caravans between China and India.

Nepal’s long and tragic civil conflict has had a serious impact on development programs in many parts of the country – including Humla. Cockburn, whose humanitarian work has won him much praise around the world, hopes to witness how the people of Humla have been living despite their many challenges -- isolation, little access to any development resources, and the political conflict, which is finally subsiding.

“One of the things that characterizes people living in difficult conditions is a very well-developed sense of how dependent we humans are on each other,” says Cockburn. “There’s a sense of community that is beyond anything that one encounters in the developed world."

“This is what allows people to survive their difficult circumstances and to support each other physically and emotionally, given the hard work and pain that they live with,” he says. “It will also be interesting to see what the impact of the war has been on that sense of community because that often has a part to play, and that means things could go either way.”

Susan Walsh points out that despite the many challenges, the communities supported by USC Canada have managed to continue their work. “The people of Humla own this work, and it’s succeeding because of their resilience and determination. They have put all their efforts, their heart and their ingenuity into it,”she says.

Village committees in Humla are actively running small-scale irrigation, organic agriculture, community health and education programs with minimal outside support.

Cockburn’s Humla journey takes place November 11-23, and will be captured by film-maker Robert Lang of Kensington Communications.

Visit Bruce’s Nepal blog at http://kensingtontv.com/kensington/content/project/26/Return-to-Nepal to see journal entries, video clips and images from Humla.

For more information:

Faris Ahmed, USC Canada (613) 234-6827 ext. 223; e-mail: fahmed@usc-canada.org

ABOUT USC CANADA

USC Canada was founded in 1945 by Lotta Hitschmanova as the Unitarian Service Committee of Canada.

USC promotes vibrant family farms, strong rural communities and healthy ecosystems around the world. With engaged Canadians and partners in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, we support programs, training, and policies that strengthen biodiversity, food sovereignty, and the rights of those at the heart of resilient food systems -- women, indigenous peoples, and small-scale farmers.

For more information visit www.usc-canada.org, or contact: Ron Cross, Communications Officer, USC Canada. Tel: (613) 234-6827 ext. 240; e-mail: rcross@usc-canada.org

November 14, 2007

From The Field

The Ottawa office of USC have not heard from Bruce and his team as of this date. A phone call to the USC office in Kathmandu indicates there is some bad weather occurring in the area at the moment, and this appears to be interfering with satellite phone connectivity. Standing by...

And now...

A rough signal was establish and the following report from Bruce came through...

We visited with a farmer today and when you see the film we end up with at the end of this you’ll see what a remarkable guy he really is.

He went to extreme lengths to establish himself as an organic farmer in this area. And that might sound strange because you might think... well... there’s people living in these remote mountains that have always grown organically, but it isn’t always that way because the corporate reach extends this far.

He is very careful to point out, and is grateful for the involvement of USC Canada in enabling him to carry out his plan.

It was an interesting encounter, and they demonstrated to us how they cleared their field of these enormous Volkswagon sized rocks that surrounded everything else around him, but he had this useable garden that he’d created out of... volcanic debris, basically.

November 16, 2007

Satellite phone call from Humla District, Nepal

It’s hard to compress the amount of sensory intake into a simple statement, but we have had a lot of response from people both here in the Simikot area and in the village we were in about the USC, about their appreciation of the work that USC has helped them do. There’s just a lot of good feeling all around about that and about a foreign presence in general. This is not a place where people are unhappy to see foreigners. They’re generous and hospitable and friendly, in spite of the fact that we’ve heard stories about the Maoist and whatnot.

One of the interesting comments that we had was from a lady we spoke to the day before yesterday. She said the increased development facilitated the capacity of women to get more money and to make their lives a little easier. The men sometimes got resentful and occasionally this would result in a drunken beating. The women were appreciative of the fact that the Maoist came in and limited the availability of alcohol in a serious way, I guess. That solved the problem of women being beaten by their drunken husbands. They like the Maoist for that. They were not so happy with the phenomenon of a group of, I presume, fighters coming in to the village and demanding to be fed, because they don’t have enough food to go around for their own children. They resented having to feed groups of Maoists, but in that one respect they were very happy with them. We haven’t actually met any Maoists yet, but we think we will in the town of Bargauon, where we’re going today. We’ll have so more say to you about that later.

Last night we had a fantastic party here in Simikot with the staff of USC Nepal, with various friends and helpers, the people that have been working with us, and some unexpected guest as well. It was a wonderful evening of dancing and laughter and a small amount of drinking. That’s got us all fired up now to go on to the next thing, go over that next mountain.

We’ll hopefully talk to you again soon. I apologize for the fact that it’s been hard to get this communication going. The accessibility to the satellite and to other technologies is very limited and very unpredictable. Hopefully we’ll speak to you again soon. END

November 20, 2007

Satellite phone call from Humla District, Nepal

We traveled yesterday. We spent a couple of days in a little town called Bargauon which is on the other side of one of the nearer mountains from Simikot where we are now. We traveled back, took most of the day, well actually that’s not true, we left in the early afternoon and got back here about dusk so it was a full afternoon’s walk to get back from this other town over pretty spectacular terrain. There are roads in parts of Nepal but in the mountains there are not what they call roads, I mean they are roads, but they’re not roads that are usable by vehicles. They’re usable by humans and animals and all of the travel that we do up here is on foot. You meet people coming and going also on foot or you’ll meet a caravan, so all of the commerce is carried on by means of pack animals – donkeys or goats are the most predominant among them… horses sometimes, too. And dzo, which are a cross between a cow and yak. We actually haven’t seen any yaks but it’s pretty exotic. The big change that’s happened in the twenty years since I was here previously is in the political arena. Two years ago “democracy” arrived in Nepal for the first time ever. It had been a kingdom up until that time and ruled autocratically by the king. Democracy came essentially because there was a Maoist gorilla war being carried on for ten years. By way of ending the war the king, the government of the day, had to pretty much accommodate certain demands of the Maoists. The Maoists don’t, it appears to me, have a huge amount of popular support but they do have some and they raised issues that people were very interested in such as gender equality, such as development-related stuff, but their vision of development was strictly local in nature, at least that was their attitude toward it. So they weren’t friendly toward UN agencies, for instance, and they weren’t friendly toward the big famous charitable agencies. Interestingly enough, USC, because in Nepal it’s USC Nepal, it’s viewed as an indigenous organization supported by the community and parent organization so the Maoists were tolerant of that and they didn’t blow up our hydro projects, for instance, whereas they went around and did blow up the government ones. There doesn’t seem to be any particular political structure in the communities themselves as far as I can see. It’s about as democratic as it could be – everybody does what they want [laughs] but they’re very conscious of each other and of the effect of their actions on their neighbors and their neighbors are not shy about letting them know how they feel about things from what I can see. In Bargauon pretty much every body’s a farmer. They all get the same time every morning and take their cows out to the pasture and do their plowing when they have to and so everybody kind of understands everyone else quite well. There seems to be a lot of friendliness as far as we can see, that may have been because we were there. I’m not sure; it’s hard to tell those things. The school that we visited had a pretty significantly high number of female students. It was remarked on by the people who were familiar with the scene ten years ago there weren’t any female students and now it looked to me like about half the students are female, which may have something to do with the Maoists and it may have something to do with the message of organizations like USC getting through to people. And proof being in the pudding too. You know I think historically parents have been reluctant to spend money to send their daughters to school but the daughters do well when they go. Anyway, for whatever reason things are changing with respect to gender equality here but there’s a way to go yet. You pass people on the paths and there’s a guy walking along with his hands in his pockets and behind is his wife and his daughter carrying huge loads of whatever. That’s a common as sight as it is to see everybody carrying loads. That’s not to assume that the men don’t work hard because they do. There’s a tendency, especially in the gentry community, I think to keep the women in the house and have them do a lot of the Joe jobs of living. We asked, for instance, how much it costs to send a kid to school for a year. Girls are subsidized by the government, now, to the tune of a thousand rupees a year. I’ll tell you what that means in a minute. But to send a kid to school costs about 25 thousand rupees a year and this is coming out of the pockets of the parents or the kids themselves as they get older and can earn money. So, the request that came from the head of the school board was for USC to support being able to hire more teachers for their high school because they weren’t going to get that kind of support from the government. The other towns, out of the five that we were in, the ladies that we were speaking to at length more than anything wanted a community hall. They wanted us to help support a community hall. This is what we’re hearing from people. Nobody’s asking for food handouts or kind of band aid-type stuff. Their asking for support for development related things. One of the things that we’ve seen in action is the improved agricultural techniques that have come with the training from USC. Everybody’s growing organic food and there’s a wonderful absence of chemical agricultural crop here. The techniques for doing that have been brought from Kathmandu by the USC staff there. We’re not being asked for agricultural help at this point because I think people feel they’re on top of that. The next level of development – okay, now we can feed ourselves, now we want to learn stuff, now we want to have a civilized society. People are sharp and they’re looking at their own best ways to use foreign aid. END

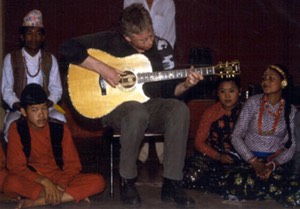

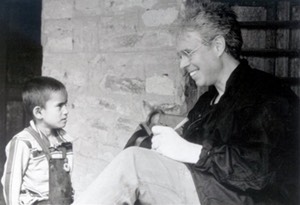

Posted: November 23, 2007. Photos by Guy Clarkson

2007 Bruce learning a Nepali peace song from Ananda in Simikot

MJ and Bruce

Posted: November 27, 2007

USC Canada

Hello Friends of USC Canada and friends of Bruce Cockburn,

As you know, Bruce has returned to visit Nepal, the country he calls "hands down the most beautiful place on earth that I’ve seen." Cockburn returns twenty years after his first visit in 1987 with the same travel companion - Susan Walsh, USC Canada’s Executive Director. Cockburn and Walsh journeyed on foot, staying in the villages of Humla district, located in the northwest corner of the country

Many of Bruce’s fans have been avidly following Bruce’s journey back to Nepal, on his Path to Nepal.

They have also begun contacting USC Canada to see how they can contribute to USC projects in the communities of Humla, Nepal.

You can give through USC’s new Gifts that Grow Catalogue. The following gifts are destined for Humla*:

The Seedlings - $25

Drinking Water - $50

Vegetable Gardens -$500

*See below for more information on Humla, Nepal and the Gifts that Grow options for Humla.

Or, you can simply make a gift to USC Canada. Please be sure to indicate in the notes section that your gift is to be directed to Humla, Nepal.

If you have any other questions, or if I can help you out in any other way, please don't hesitate to email me directly at bmcfarlane@usc-canada.org.

*GIFTS THAT GROW - GIFTS FOR THE PEOPLE OF HUMLA

Seedlings $25, Humla, Nepal

We are looking to raise $625 for seedlings in Nepal, a total of 25 gifts of $25. It costs one cent for one seedling of ‘Atis’ (Aconitum heterophylum) - a medicinal herb that’s used in both the traditional and modern medical practices in Humla. Each seedling, produced by a group of local farmers in a nursery, will be given to a farmer, to be transplanted on farmers’ local fields. Goal = 25 batches of 2000 seedlings.

Drinking Water $50, Humla, Nepal

$50 will provide two households with potable drinking water. USC’s goal is to raise $3,000, which is a total of 60 gifts to provide a Drinking Water System that will serve 132 households or 800 people.

Vegetable Gardens $500, Humla Nepal

Our goal of receiving two gifts of $500, for a total of $1,000 will assist women in six villages to plant and maintain healthy vegetable gardens that improve the nutrition of their families and generate income through the sale of surplus produce. The gift includes the cost of tools and training on food processing. The cost per 3 villages is $500.

November 28, 2007

CBC Interview

Bruce was interviewed by phone in Nepal by Jian Ghomeshi for the CBC Radio program called Q.

JG: Hello, Bruce.

BC: Hey, Jian, how are you doing?

JG: Good to have you with us. Where are you right now?

BC: I’m in the city of Pokhara at the moment. The work part of the trip is done and we have a few extra days at the end now to just kind of relax and take stock and get ready to come home.

JG: A lot of people would have heard of Katmandu. Is Pokhara actually a town with a sizable population?

BC: It is. It’s kind of the second city of Nepal.

JG: Bruce, take me back twenty years. How did that first 1987 trip get coordinated? Had you always wanted to go to Nepal?

BC: Actually my brother was here back in the 70s and said it was the most beautiful place he’d ever been. At the time he spent a couple of years traveling around the world in a kind of hand-to-mouth manner and loved Nepal and found it to be a great relief from just about everything else he encountered. It was kind of in my head as that, but USC came along – I’d been working with USC Canada since early in the 70a anyway – and somewhere in the mid-80s they approached me and said “We’d like you to go somewhere for us.” At the time I’d been to Central America with OXFAM, I’d been a couple of other places and I was starting to get a reputation for doing that sort of stuff. They asked me if I would go to any one of the countries in which they were operating – go around and have a look at their projects and try and help them do some education and fundraising around that. Looking at the list of possibilities I picked the one that was least likely to be a war zone at the time, and that was Nepal.

JG: I’m aware that it inspired a couple of Nepal-inspired songs… Tibetan Side of Town and Understanding Nothing, that were on your 1988 album Big Circumstance. I wonder in the ’87 trip what your overwhelming impression of Nepal was in terms of the people and their interaction with each other and with you.

BC: We were received with the greatest hospitality everywhere. People went out of their way to offer the best of what they had, which in many cases, was not much. Their were funny things. In one village we went into, “we” being Susie Walsh, who at the time was project officer for this area with USC… we went into a village and they had built a latrine, presumably because were coming because it was brand new and the lumber was still kind of fresh. It was really well-built. It was right smack in the middle of the town square and it was the only building in town with an electric light bulb. We had dinner with the important folks in the town and after dinner we’re invited to make use of the latrine [laugher]… and it’s a show.

JG: The well-lit latrine.

BC: It was a well-lit latrine and it was the only thing going… it was the only show in town. It was great. The little kids were kind of lined up around to see what happened when someone went in the latrine.

JG: You’ve been known for all kinds of performances.

BC: [laughter] Yeah, I know. That’s one we haven’t been able to share with the world, yet.

JG: Take it on tour.

BC: [laughter] That’s a thought.

JG: You’ve talked about the sense of community that you saw in Nepal in what you’ve written in the past. Can you explore that a bit?

BC: In one village we were in, for instance, which was a little better off than some of the other ones… there was a school in this village… there is a school in this village, a grade school. The elders of the village had decided that they needed a high school. So, they approached the government for permission to set up a high school. The government gave them permission but they didn’t give them anything else. No money, no teachers, nothing. So, the village went ahead and built a high school. They hired teachers on their own ticket. When we went into this village one of the things that they requested from USC was that they get support for paying teachers salaries for the high school. Of course the government of Nepal at this moment is not very effective because it’s in kind of limbo having become democratized a couple of years ago, but having been unable to agree on how to hold elections between the extremely disparate parties involved. So, there’s a kind of a state of anarchy in a way and nothing is getting done, especially at the level of poor villages in poorer parts of the country. These folks are on their own, but “on their own” means they went ahead and did it. If you think about it, I mean, it’s possible to imagine a community in Ontario doing a similar thing, but it seems like a stretch.

JG: Bruce, I want to ask you about your imperative. I know your music and you politics and your traveling are all intertwined, but what do you see your role as on these trips? Are you an advocate, a witness, a celebrity… where do you see yourself?

BC: I see myself as a witness. I see myself as an advocate. I’m a helper. There are people doing good work in places like Nepal, and somebody in my position can sometimes help those people to do their work by helping with fundraising, by raising awareness among my audience, whoever that happens to be, about the reality that the people who are experiencing these difficulties are people just like us. They are people who have lots to teach us, too. It’s not s one-way street. It’s important that we not think of it as a kind of handout situation because that sense of community that we talked about awhile ago is something that we could all benefit from having a little more of in the developed world.

JG: It seems like in your songwriting, in your craft, in your artistry, you’re directly inspired by where you travel to and what you experience. I’m thinking of songs like Lovers in a Dangerous Time, If I had a Rocket Launcher. I’m thinking about the recent albums you’ve made after trips to Iraq. Do political songs need to come out of first-person experiences for you? Do you need to travel for that inspiration?

BC: I’m not sure I need to travel for it, but they do have to come from personal experience or personal feelings, let’s say, and the feelings are usually engendered by some kind of experience. I have to have a strong emotional response to something going before the creative process gets underway.

JG: Is that part of the reason you travel, to inspire you as an artist to reflect on what you see?

BC: It may be, but I choose not to think of it that way [laughter] because I think, for instance, that coming to a country where people are in trouble and looking for song material seems a bit perverse. Of course, everywhere I go whether it’s in North America or elsewhere, I always hope to get songs and I hope I’ll run across things that trigger that process. It happens that a lot of the time it has worked out that way in countries like Nepal.

JG: Bruce, thanks. Thanks for joining us. Take care of yourself out there.

BC: Thanks for having me on your show.

JG: Bye-bye.

BC: All the best.

END.

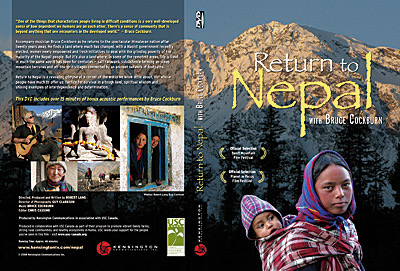

Return to Nepal with Bruce Cockburn

Kensington Communications, the company responsible for the filming and production of Return to Nepal, has the DVD available for purchase and excerpts from the DVD on their website. It contains bonus music tracks of Bruce playing live "in the field." The DVD running time is approximately 46 minutes. A portion of the proceeds will be donated to support the programs of USC Canada.

Bruce Cockburn Film to air across Canada

Return to Nepal, featuring USC’s work, will air on CBC Documentary Channel

Travel with Bruce Cockburn as he returns to Nepal after twenty years away. The CBC Documentary Channel will air the broadcast premiere of Return to Nepal, a new documentary film chronicling Cockburn’s recent visit to the spectacular Himalayan nation. The film will show at the following times:

Monday, January 19, 2009 at 7pm and 10pm

Tuesday, January 20, 2009 at 1am, 9am, and 1pm

Wednesday, January 21, 2009 at 5am

In November 2007, Filmmaker Robert Lang followed the musician as he travelled to Humla – a region nestled in the Himalayan Mountains. There he found a land where, while much has changed, life is still often lived in much the way it has been for centuries. Farmers still work the steep mountain slopes and live in remote villages connected by an ancient network of footpaths.