February 16, 2015: On January 15, 2008, I interviewed David "Fox" Watson from his home in Black Mountain, North Carolina. The interview has gone unpublished until now. I was waiting for the right time and, with the recent release of Bruce's memoir, I think that time has arrived. I spoke with Fox again on February 9, 2015. He is still living in Black Mountain and enjoying all the things he loves. The following is from our conversation in 2008. -Daniel Keebler

June 1, 2019: See the update to this story at the bottom of this page.

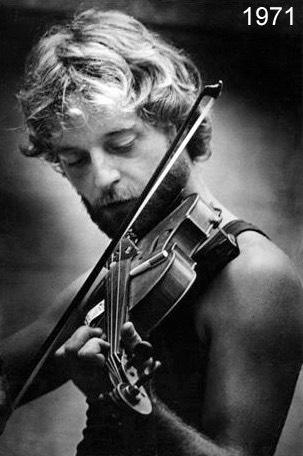

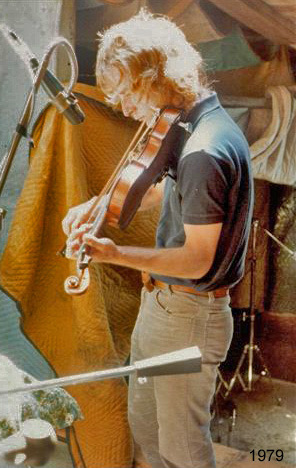

FW: I met Bruce when he was at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte [in the fall of 1968] playing a coffeehouse concert [at the Bitter End Coffee House] with a group called 3’s A Crowd. He had a beautiful redheaded singer [Colleen Peterson]. The thing that I remember was that I opened for them and he was watching me play and then when they came out I was watching them. We were both equally astonished that we had bumped into another person that was basically oriented toward the guitar, acoustic guitar, in the same cosmos – with the same cosmology – which was an alternating thumb between the sixth and the fourth and the fifth string. That was what we would keep rhythm with and then we would play melody with the first and second fingers. That was something that I picked up having grown up in North Carolina. I was born in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania (February 24, 1950], but we moved to Louisville, Kentucky, when I was six months old. Then, when I was ten years old, we moved outside of Charlotte, North Carolina. During that period I was exposed to, growing up in the country, all kinds of southern music. I just instantly latched on to it, much to the chagrin of my mother who was a classical pianist who had been investing large sums of time and money in trying to get me trained as a violin player. I was not big enough to do sports. It was fine with my father that I was into music. He was just glad I was into something. I was just taken by the music, which was everywhere. It was a lot of Piedmont Blues that you could hear on both banjo and guitar. I was first exposed to that at about twelve, and at thirteen I decided I was going to play guitar. I was going to basically figure out a way to get out of playing violin. But, I was always listening to what people would be playing on violin or fiddle in the area I grew up in outside of Charlotte, which is now a big suburb of Charlotte. At the time it was called Steele Creek in Pineville, North Carolina. I was always listening to what people would play on acoustic instruments. At fifteen my father passed away, suddenly, out of the blue. They didn’t know what to do with me so they shipped me off to a performing arts school in Winston-Salem, which was really fortunate for me because it was my first exposure to music other than just southern music. It absolutely kind of sealed the capsule for me because I knew after nine months in a strict music conservatory that I was never going to be a classical musician, so I just got deeper into southern music. This would have been 1965. I knew there was some sort of a folk scare of some kind happening somewhere in the world, but I was going to school in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and I was in school in a very cloistered music conservatory, so it really wasn’t very relative at that point. I remember at the end of the year that you had to reapply for admission, and that would have been my junior year. The director of the school, Vittorio Gianinni, who was a renowned composer, sat me down and said, “I know that you’re not going to be a classical musician and you probably do, too.” And I said “Yeah, I do.” He said “I know that you’re a really good folk guitarist, so maybe that’s what you should do.”

DK: How old were you then?

FW: I was sixteen. I was so relieved, but at the same time so frightened by the fact that I didn’t have this sanctuary to remain in. I left after one year and went back to Charlotte, and then about half the year I was out of high school. I just left and moved to the mountains of North Carolina when I was sixteen. When I moved to the mountains it was with a girlfriend, who had just happened to inherit three or four thousand dollars, which in those days was a fortune. We had gotten a little cabin in the mountains around Burnsville and all I did all day long was play music – just play guitar, and I started playing banjo by that time. I think being in the mountains really kind of leant itself to me listening more seriously to the fiddle tunes that were being played. I think about this same period of time I began really getting wistful, very nostalgic, for my father. He was really a wonderful guy who loved Scottish music. From the time I was ten years old we would go to these Scottish Highland games in different places – in the mountains of Georgia or the mountains of North Carolina. So, I was hearing bagpipe music from the time I was nine and ten. I sort of had my feet in Dixie and part of my head in the Highlands of Scotland. That had a lot to do to influence what I regarded as a direction I wanted to go in as far as being a guitar player. There were people like Doc Watson who were on the scene, and I was influenced a lot by Doc. I was considered to be a very good flat picker around ’65. I just seemed to have this unresolved need to pull together fiddle tunes that could be played in an open tuning like a banjo. I was beginning to learn to play banjo around the age of sixteen, which is in an open tuning. I thought why not just lower the guitar and do an open tuning and play it liked I’d heard some of the blues players in and around North Carolina play, but use this alternating bass like Elizabeth Cotten used. Then, you overlay on top of that my own background, which was this strange mixture of America and Scottish. I decided I could play fiddle tunes that you might play on bagpipe on guitar. So, by the time I met Bruce – which is jumping ahead three or four years to 1968 – I had left the mountains and the girlfriend and had decided the only thing I knew how to do, because I hadn’t even finished high school at that point, was to go on the road and play music. That University of North Carolina job was one of the best paying and one of the first jobs I think I ever played… and, boom, there’s Bruce Cockburn. I knew the minute I heard and saw him that I was in the presence of somebody who was going to do something interesting, musically. He would take Beatles tunes… [pauses] He would take the cover tunes that the group was sort of required to do, because he was just beginning to really write at that time. I’m sure he only had so much material, but he had a real knack for arranging tunes that other people had written, like Lennon and McCartney. They [the covered songs] were just different. It would be the Beatles à la Bruce Cockburn’s finger-picking, funky acoustic guitar style. Nobody played stuff like that. Having had the experience of being raised in this weird family of partly classical musicians, but being raised in the south, you always heard this wonderful folk music everywhere. I knew immediately that he was doing something different. There was just this edge to his playing. I just felt this kinship with this guy because he played this alternating thumb style and he had a name like Cockburn… and I knew that was a Scottish name first thing out of the gate. I had had some cousins that were Cockburn’s, spelled the same way. After they played I was just stunned. I just couldn’t believe it. I’d never seen anything like this. He and I went back to his hotel room I think and we sat and played music all night. I played everything I knew and he played a lot of things. He looked at me at some point and he said “You know, you really ought to come to Canada.” I didn’t have anything going on. I had a couple of fiddler’s conventions I was going to go to. I think it was about a month later I showed up at the Union Grove Fiddler’s Convention in Union Grove, North Carolina. It was fairly well-known all over the United States and drew participants from all over. I remember there was a pharmacist there from Long Island. He asked me what I was doing and I said I was going to try and make a living playing music but I needed a ride north because I thought I’d go to Canada. He said “I’m going to Long Island. You can ride all the way up there and we’ll put you on a ferry and get you headed in the right direction to the bus station and you can catch a bus the rest of the way.” So, that was how I got to Canada … via the Union Grove Fiddler’s Convention, to Long Island, to Vermont and then on up to Toronto. Bruce was living off of … I think it was Bloor and Yonge at the time. Somewhere close to Bloor and Yonge. He was living with his girlfriend, Kitty. She was just this wonderful girl, who I asked him about the last time I saw him. I think they had a daughter together.

DK: Jenny.

FW: Jenny. Who I hope is doing well.

DK: Kitty and Bruce parted ways around 1980.

FW: I’ll be darned. I’m amazed they stayed together that long. Because, I’ll tell you something, trying to maintain a relationship during that period of time – and Bruce was very, very sensible in how he treated other people. He was always very up front with everyone about what he could and could not provide. He never, never came at you from some weird direction. He was very straight up… “I can do this, I cannot do that. If I were you I’d make plans to do this or that.” He was wonderful that way. When I first met him I think I stayed at his apartment. It seems like I stayed here for a couple of weeks but it may have only been a week or two, or it may have three or four nights… I don’t know. I ended up somewhere else in Toronto. We went at what we were doing with all the relish of a couple of musketeers. I was going to play guitar with him and we were going to meld these two cool guitar styles together. We did everything we could do to make that happen but… I was a guy that played a certain kind of tune. It was best characterized by Bruce as “fiddle tunes on guitar.” That was it. I didn’t know what to make of a lot of the melodic things that he would do in his tunes. He would play melody with his first and second fingers and he would depart from that 6/4, 5/4, 2/4 and 4/4 time… he would do all kinds of times. I just didn’t have the repertoire to follow what he was doing and I knew that there would probably never be anybody that would be able to follow exactly what Bruce was doing. He was just going to have to do this on his own. He actually figured it out before I did. He said “I’m just not sure if this is going to actually work.” I said “I know you’re right. Now, here I am in Canada and I love it up here so whether we work together much longer or not I’m gonna stay.” It was a great time to be up there. Growing up in the south all I knew about Canada was cold fronts and hockey players. I didn’t have a clue what was up there, until I got there. I remember my father telling me as a child that I needed to go to Canada as some point in my life. I asked him why and he said “Because they are the most civilized people on earth.” I asked him what he meant and he said “They have the most beautiful women and wait until you see the architecture. You’ll love it up there.” The minute I got there I realized what he was talking about. I stayed there I think for a year and a half to two years. The only reason I ever came home was just because I really could not get a visa to work there, and I didn’t know how to do anything other than play music at the time. I was absolutely astonished when I found out that Bruce had written two songs sort of in memory of the little influence that I had over his playing. His musical style was very well formulated by the time we met one another. So, it wasn’t like I influenced how Bruce ended up playing I don’t think. He already had his style down. His style and my style just happened to be in the same vein. I think Bruce has been influenced by Bert Jansch, from Pentangle. Someone had stuck one of his LPs in my hand when I was at the music conservatory. I remember hearing it and thinking “Oh, I get that.”

*****

At this point I read to Fox from the Ottawa Folklore Centre’s Bruce Cockburn songbook called “All The Diamonds,” which included comments from Bruce on the songs Sunwheel Dance and Foxglove.

Sunwheel Dance: Touring the Carolina’s in the ‘60s with a band of questionable virtue, met a young man named Fox Watson. Given to rendering fiddle tunes on the guitar in a graceful finger style that seemed to float like the wings of a gull. I’d never thought of trying to play like that, but it looked and sounded attractive, so I fooled around with what I could remember of the technique and came up with the first of several guitar pieces – Sunwheel Dance.

Foxglove: This was the second guitar piece I made up. The title, aside from being the name of the plant digitalis, is a sly acknowledgement of Fox Watson’s influence.

*****

FW: How remarkable. I’m speechless. That’s so cool.

DK: Bruce is still very straightforward and honest in his dealings with others.

FW: Whether you like it or not. I didn’t like it a lot of the times but it was always honest and I’m so grateful to have had a friend like that, because I was buffeting myself at that period of time in my life. In fact I even told Bruce this the last time I saw him. I was buffeting myself through a lot of pain over the death of my father. I could tend to be rather grandiose in an attempt, looking back on it now, to throw up some armor around myself. I really had no support system and I don’t know if Bruce did either because his father was a physician. I think they were probably like my folks, they were encouraging in the sense that their kid was doing something in the arts but they couldn’t have imagined that their son would ever be a singer/songwriter and that’s what he would do for a living. Like my parents couldn’t have imagined that I would attempt to make a living at music. He [Bruce] would just occasionally go “You’re just absolutely full of bullshit. You gotta stop it.” When he would do that I would just snap back and go “Wow, that’s great you just said that.” I finally left Canada because I had to come back to the United State because my visa was up. I went from playing with Bruce to playing with Jerry Jeff Walker, and I wasn’t sure what kind of impact I was making. I’m very touched that Bruce would give me that kind of credit.

DK: Your name is known among most all hardcore Cockburn fans. The song, Foxglove, is an all-time favorite among the roughly thirty albums. In fact it is has been used in some courses for study. It’s difficult to play.

FW: I’m speechless. I wish my daughter [Kellin Watson] could be listening to this conversation because she’s a very prolific singer/songwriter and a brilliant musician. I would just love to have her hear this.

DK: When was the last time you saw Bruce?

FW: I think it was maybe two years ago. He tried to call me last year but I was not at home until the day after his concert. He left this beautiful message to let me know there was a ticket for me, my wife and my daughter. It was after his album Life Short Call Now came out. I thought how apropos that Bruce would call at the last minute because life is short… and he did call. It really meant a lot to me.

DK: What have you done for a career since the early 1970s?

FW: I came back from Canada and I played with Jerry Jeff Walker for awhile and also hung around up in Woodstock, New York, and played with just about everybody you could play with. But my style never really fit in with anybody. It was the early 70s. I don’t know how Bruce made it through that period. I don’t know how anyone made it through that period. From the late 60s where there was this incredible fascination with acoustic guitar to the mid-70s where you had this horrible disco shit… people like Bruce just damn near fell off the face of the earth. If he had not a hit with Wondering Where The Lions Are and had not been writing as hard as he was writing it might have been just impossible because it did get really difficult in the mid-70s to make any money whatsoever playing acoustic music. People just didn’t want to hear it. So, I came back to North Carolina eventually and met my old high school sweetheart, who I’m still with. We ended up moving to the mountains and the second my daughter was born I realized the party was over and I had to go to college. I had to finish high school – go to college, graduate school, post graduate school. So, I spent the next twelve years of my life in one form of school or another basically studying psychology and working with children. I really just gave music a heave… until about seven years ago. As soon as I retired, with a lot of money I had saved from real estate investments, I started putting up Canadian kids [Canadian bands that would come to play nearby venues or that were on the road needing a place to stay]. I always felt like, if I ever had the opportunity to do for Canadians what they had done for me when I was most vulnerable, which was just share their spiritual charity with me, feed me - I would. Leon Redbone’s mother took care of me for weeks when I was sick. There were so many people like that. Many of them were Bruce’s friends. Ian and Sylvia… I lived with Valerie Fricker, Sylvia’s sister, for awhile. She was so wonderful to me. Canadian’s are just the best people in the world. So, when I actually came into my own financially I really did create this southern, Canadian embassy. As these kids would roll through town they were just interested in bed and breakfasts, a safe place to sleep. My wife and I became the den mother and den daddy for all these Canadian kids. I think the word sort of spread that Fox and Bébé are safe and he’s a psychologist and he’s got lawyers, guns and money, and if our kids get busted while there down there in North Carolina they’d be better off being in touch with Fox and Bébé.

Recording has been out [for me] because I’ve taken the money I would have spent on myself and let my daughter chase her dream, and she’s doing quite well. But the next project, I’ve let everyone in the family know, is going to be my album. The name of my album is going to be Life’s Over Call Later.

END

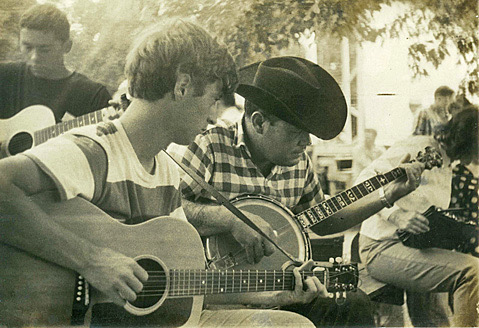

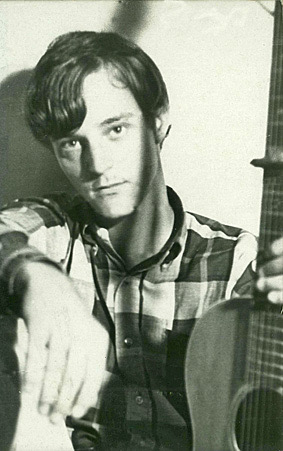

(C) Fincastle, VA - circa 1967, with unknown banjo player

(R) Fincastle, VA - circa 1967 with Dan MacCorrison

North Carolina - circa 1967

North Carolina - (with guitar) Summer 2014 Photo: Julia Campbell

In 1977 Smithsonian Folkways released a 15 track CD called Fishers Hornpipe and Other Celtic Traditional Tunes, by Fox Watson and Laurie Diehl. MP3 files are also available. Details, track listing, download the liner notes and purchase here. (With thanks to Richard Hoare.)

Fox was interviewed in July of 1977 by Dr. Louis Silveri at the University of North Carolina in Asheville. Find the 85 page PDF of that interview here.

UPDATE: June 1, 2019

On May 15, 2019, I rolled in to Black Mountain, North Carolina. I was in the midst of a three week trip that included attending Bruce’s shows in Beverly, Massachusetts and Waterville, Maine. I was in Black Mountain to visit with Fox Watson. This would be our first in-person meeting. We enjoyed a nice sit-down conversation at his home before we headed to the Blue Ridge Biscuit Company for some midday vittles. Afterward we returmed to the house and were treated to some guitar and banjo playing. Although our visit was far too short (about four hours), it was a most rewarding time. Big thanks to Fox and Bébé Watson for their hospitality.

Photos of my visit with Fox can be found here. (Opens in a new window.)