December 3, 2018

FYI Music News

The LYNNeS, Pharis Romero Win Multiple CFMAs

The 14th annual 2018 Canadian Folk Music Awards (CFMAs) were awarded over two nights (Nov. 30 and Dec. 1) at The Gateway (SAIT) in Calgary. The spoils were evenly distributed, with only The LYNNeS and Pharis Romero winning multiple trophies.

The Friday night event, hosted by James Keelaghan and Benoit Bourque, featured performances by Andrea Bettger, Danny Boudreau, Ben Heffernan, The LYNNeS, West of Mabou, and Dana Wylie. Ten awards were handed out throughout the evening, including the Slaight Music Unsung Hero Award, presented to Terry Wickham, longtime Artistic Director of the Edmonton Folk Music Festival.

Saturday evening's event, again hosted by Keelaghan and Bourque, featured performances from Matthew Byrne, Jack Pine & The Fire, Little Miss Higgins, Quantum Tangle, Annie Sumi and The Lifers, and Winona Wilde. Another ten awards were handed out.

Here is a full list of winners:

Traditional Album of the Year: Matthew Byrne - Horizon Lines

Contemporary Album of the Year: Donovan Woods - Both Ways

Children’s Album of the Year: Edgar, LeBlanc, Cool, Farmeur, Vishtèn, Savoie, Butler - Grand tintamarre ! - Chansons et comptines acadiennes

Traditional Singer of the Year: Pharis Romero (of Pharis & Jason Romero) - Sweet Old Religion

Contemporary Singer of the Year: Rob Lutes - Walk in the Dark

Instrumental Solo Artist of the Year: Jean-François Bélanger - Les entrailles de la montagne

Instrumental Group of the Year: The Fretless - Live from the Art Farm

English Songwriter of the Year: Lynne Hanson, Lynn Miles (of The LYNNeS) - Heartbreak Song For The Radio

French Songwriter of the Year: Christian Bernard, Anik Bérubé, Natalie Byrns, and Frédéric Joyal - Le soleil en bulle

Indigenous Songwriter of the Year: Shauit - Apu peikussiakᵘ

Vocal Group of the Year: Pharis & Jason Romero - Sweet Old Religion

Ensemble of the Year: The LYNNeS - Heartbreak Song For The Radio

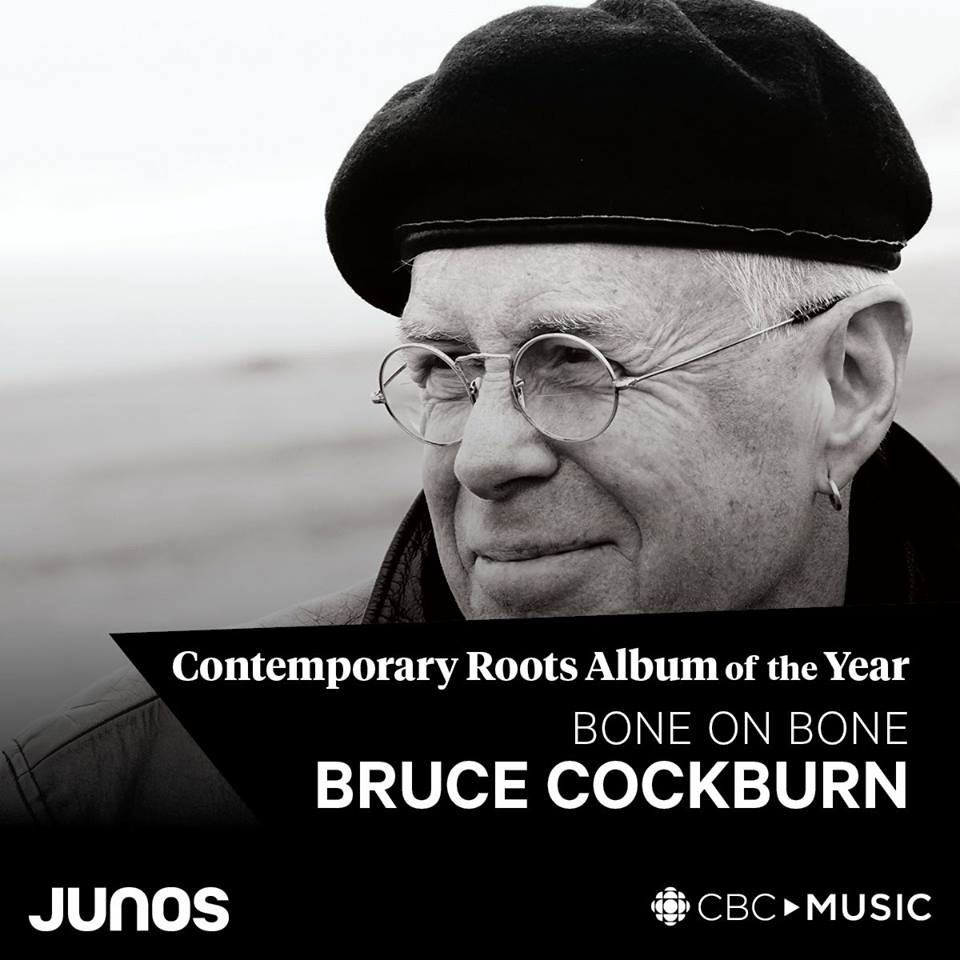

Solo Artist of the Year: Bruce Cockburn - Bone On Bone

World Solo Artist of the Year: Eliana Cuevas - Golpes Y Flores

World Group of the Year: Autorickshaw - Meter

New/Emerging Artist of the Year: Raine Hamilton - Night SkyAerialists - Group Manoeuvre

Producer of the Year: Steve Dawson - Same As I Ever Have Been (Matt Patershuk)

Pushing the Boundaries: Beatrice Deer - My All To You

Young Performer of the Year: Nick Earle, Joseph Coffin (of Earle and Coffin) - A Day in July

Slaight Music Unsung Hero Award: Terry Wickham

November, 2018

The Al Purdy Songbook celebrates the work of an iconic Canadian poet. Along with its sister project, the film “Al Purdy Was Here,” it was inspired by campaign to save and restore Purdy’s A-Frame home as a writing retreat for a new generation of artists.

The Music and the Artists

by Songbook Producer Brian D. Johnson

Jason Collett, who’s been combining literary and musical talent for years in Jason Collett’s Basement Revue, agreed to co-produce the Songbook without a moment’s hesitation. He also came up with a soulful track called Sensitive Man, named after an ironic boast from Purdy’s iconic tale of a barroom fight, At the Quinte Hotel. Featuring The Band’s Garth Hudson on organ and accordion, Jason’s vocal captures Al’s yearning spirit in a droll yet vulnerable portrait of an artist who was “born a middle aged man with belly and ballpoint pen” who “built a frame to fill with mythology/late night brawls and epiphanies/a northern nobility that we couldn’t quite conceive/where a country could imagine itself.”

Bruce Cockburn was one of several contributors already deeply familiar with Purdy, and he embraced the challenge as if it were something he’d been itching to do for years. In 3 Al Purdys, a rousing six-minute epic, Bruce lets Purdy’s words come tumbling through the verses as if poured from a pitcher of draft. A generous portion of his lyrics come straight from Transient, Al’s 1967 poem about hopping boxcars on the way to Vancouver as a teenager. The song’s refrain—I’ll give you 3 Al Purdys for a twenty-dollar bill—was inspired by Bruce’s distant memory of a poet selling books on a Toronto street corner. That’s not something Purdy was ever known to have done, but it evokes the scrappy persona of a poet who could connect with the street. Bruce is the only Songbook artist who tried to capture Al’s persona in his voice, adopting a gruff swagger quite unlike anything we’ve heard from him before. This was the first song Bruce had written in two-and-a-half years, ever since becoming a father, and it kindled a new burst of songwriting that led to his 33rd album, Bone on Bone and 13th Juno Award.

Doug Paisley was a teenager when he met Purdy at a poetry reading at the Red Dog Tavern in Peterborough, Ontario. He had him autograph a pack of rolling papers, and became a lifelong fan, amassing a personal collection of rare editions. Doug’s song, Transient, takes its title from the same poem that Bruce Cockburn draws on, and channels Purdy’s experience riding the rails. But it’s a more intimate ballad, capturing the romantic side of a young man who has his eye on the horizon while his heart pulls him home. Doug recorded the song twice, first for the cameras, as he sang it solo with his guitar in his living room, then in the studio with a band. In the film, we merged the two versions to forge a soundtrack for Al’s early years.

Felicity Williams, like Doug, encountered Purdy at a pivotal moment in her teens. Years before we approached her, she had already written and performed a suite of songs adapted from Al’s poems. It was her idea to record in the A-frame. She arrived with a back-up vocalist and a jazz trio. A vibraphone player laid out the wooden slats of his instrument under the A-frame rafters, which once had once covered the floor of a school gymnasium. Felicity recorded two songs that day, both adaptations of single poems “The Country North of Belleville” and —”Woman.” The latter session was featured in the film, and the “Woman” session can be found in the DVD’s special features.

Sarah Harmer recorded “Just Get Here” in the living room of her country home north of Kingston, as cameras captured the moment for the documentary. It was the first time she’d really performed it for anyone. There was just her, accompanying herself on piano, still getting the hang of the arrangement, and the tension was palpable. Although Sarah didn’t know Purdy, she knew his neck of the woods, and some of the writers who frequented the A-frame. Drawing on various Purdy poems, her song celebrates the casual romance of a hearth off the beaten track that would draw artists to its door. “That felt familiar for me,” she says, having lived in a house “that put up tons bands that came through—I know that feeling of a place where

people come and go and music and art is cultivated.” Sarah’s song, which became the serene centrepiece of Al Purdy Was Here, is about the “here.”

Greg Keelor, another Ontario troubadour with a rural home, takes a departure from the country rock sound of Blue Rodeo with Unprovable. It’s the one flat-out rocker among the original tracks commissioned for the Songbook. Curiously, out of Purdy’s entire oeuvre, both Greg and Felicity Williams alit on “Woman,” a delicate 11-line poem from his 1994 collection, Naked With Summer in Your Mouth. But Keelor’s sun-blasted anthem could not be more different from Felicity’s ethereal jazz number (a video of which can be found on the DVD special features).

Snowblink, aka Daniela Gesundheit and Dan Goldman, came to the Songbook as a singer-songwriting duo discovering Al Purdy for the first time. After sifting through the 591 pages of Purdy’s collected poetry, they plucked some sparse lines from Al’s poem Arctic Chrysanthemums to compose the haunting rhapsody of Outdoor Hotel. It unfolds with a childlike aura of pure revelation. In the film, the song plays under a scene in which Eurithe Purdy visits the A-frame to meet a young poet couple that has moved in with their baby. The melody, as innocent as a lullaby in that context, takes on eerie overtones when it’s stripped of its vocals, and used to underscore Margaret Atwood’s ominous reading of Purdy’s Wilderness Gothic.

Margaret Atwood found time between being a prolific author, an ambassador for the Handmaid’s Tale, and an unflagging activist, to serve as one of the A-Frame campaign’s most dedicated supporters. In Toronto’s Pilot Tavern, she reminisced about her old friend Al for the film then shot some pool. Later, in the book-lined basement office of her home, she recorded a reading of Wilderness Gothic. After the first take, which was flawless, I asked if she would do a second take just to see where it might go. She agreed, only after telling is us it would be no different. She was right. She’s always right. We used the first take.

Dave Bidini was turning Purdy’s poetry into music long before the Songbook was conceived. Among singer-songwriters, he may have been the first responder. As much author as musician, he became familiar with Purdy when he was working with McLelland & Stewart, Al’s publisher at the time. “His books were always around,” Dave recalls. “I couldn’t believe that Naked With Summer in Your Mouth wasn’t written by an 18-year-old.” (Purdy wrote it at 74). Dave slipped a sample of Al reading the last three lines of “Wilderness Gothic” into “Me and Stupid,” a track on the Rheostatics 1994 album, Introducing Happiness. And he recorded Say the Names with the angelic Billie Hollies, for his 2014 Bidiniband album, The Motherland. Opening with Purdy reading some lines from Necropsy of Love, it drifts into a choral incantation of him hailing Indigenous place names versus their colonial substitutes. Published a year before his death, “Say the Names” was one of Purdy’s last poems. Before “Voice of the Land” would be engraved on his tombstone, he reminds us that the real Voice of the Land belongs to Native Peoples, and flows directly from Nature—”you dreamed you were a river/and you were a river.”

Gord Downie, like Bidini, fell under Al’s influence early in the game. Next to Leonard Cohen, it’s hard to think of a major Canadian artist who moved so promiscuously between poetry and songwriting. In 2002 he starred in a short film dramatizing At The Quinte Hotel, Purdy’s bittersweet yarn about a moment of truth in a tavern brawl. He Songbook offers his live performance of it at The Purdy Show. Before his death, Downie also offered up “The East Wind,” a Purdy-influenced song he’d recorded with the Country of Miracles for their 2010 album The Grand Bounce—with a couple of lines from, once again, “Necropsy of Love.”

Neil Young was approached to write a Songbook number. For inspiration, we sent him Al’s “My ’48 Pontiac,” a noir chronicle from the viewpoint of a car in a junkyard. Neil liked the poem, and the project. He never got around to writing a

song, but graciously donated his 1971 Massey Hall performance of Journey Through the Past to the film’s soundtrack.

Leonard Cohen met Purdy in Montreal in the 1960s. They were never close, and as poets they were from different planets. But they shared a friend in poet Irving Layton, and Cohen’s enduring respect for Purdy was clear when he stepped up as one of the first luminaries to make a substantial donation to the A-frame campaign. I thought of asking him to read “Necropsy of Love,” for the film, but it seemed too obvious. This spare poem about love and death, which Al wrote in his early 40s, reads so much like a Leonard Cohen poem to begin with. So I sent him “The Country North of Belleville”, hoping to create a canonical moment for Canadian literature. He declined, saying he would need help pronouncing all those Scottish names, and besides, he didn’t understand the poem. I finally sent him “Necropsy of Love,” and Leonard wrote back, “I’ll give it a shot.” Indeed. In early October 2014, while recording his final album, You Want It Darker, Leonard found a moment to make Al’s words his own with heartbreaking and gravity and grace.

Casey Johnson composed and produced the original score for Al Purdy Was Here. With performances by songwriters occupying so much of the movie’s musical real estate, the score had to play a constrained and specific role. Casey’s method was right in tune with Purdy’s desire for authenticity: he recorded the entire score in his home studio using vintage analog equipment. The Songbook’s final track, “Cowboy,” was created for a sequence early in the film that establishes Al’s character as a laconic outsider striding into the quiet saloon of CanLit and creating a stir. Sailing over the track is David Chan’s sublimely lazy, cantina-like trumpet. David prefers to play outdoors, so Casey set up a microphone on the sidewalk and wired him into the studio.

Al Purdy Bio:

Al Purdy was born December 30, 1918 in Wooler, Ontario and died April 21, 2000 in Sidney, BC. He has been called the first, last and most Canadian poet. “Voice of the Land” is engraved on his tombstone. But before finding fame as the country’s unofficial poet laureate, he endured years of poverty and failure. Dropping out of high school at 17, he rode freight trains during the Great Depression, worked odd jobs, and served in the Royal Canadian Air Force during the Second World War.

Purdy lived all over the country, labouring in mattress factories. In 1957, he and his wife Eurithe built an A-Frame cabin near his birthplace in Ontario. There, after two decades of writing what he admits was bad poetry, he found his voice, and finally broke through with The Cariboo Horses (1965), which won the first of his two Governor General’s Awards for Poetry.

Purdy published 33 books of poetry, a novel, a memoir, and nine collections of essays and correspondence. In 2008, nine years after his death, his statue was unveiled in Toronto’s Queen’s Park. Then, after a robust fund-raising drive, the Al Purdy A-Frame Association bought and restored the A-Frame, and launched a writing residency program in 2014. The A-Frame project inspired both the film Al Purdy Was Here and The Al Purdy Songbook.

November 16, 2018

Bruce Cockburn - Solo - Three Dates in November 2018 – England, United Kingdom

Liverpool Philharmonic Music Room – Thursday 8th

Band on the Wall, Manchester – Friday 9th

St Pancras Church, London – Saturday 10th

Observations and comments from Richard Hoare

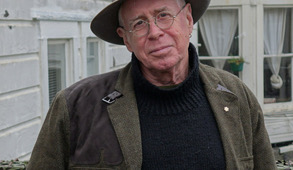

Bruce has been performing groups of solo dates since April 2018 and he wound up the current batch in the UK last week after 42 dates. His last visit to these shores was in October 2015 when there was no new album to play although the then latest release was the box set to accompany his memoir. This time Cockburn included more than half the songs from the most recent album Bone on Bone (2017) re-arranged for solo performance.

The high-ceilinged Liverpool Philharmonic Music Room was full with an audience of about 250. The attentive and quiet audience provided the best gig of this trio of dates. Bruce wore a green shirt and tie and a very cool thin blue coat with chrome zipper pulls. Cockburn kicked off, on six string Manzer, with the opening track from Bone on Bone, States I’m In with some stinging guitarwork. He then settled in with Lovers In A Dangerous Time before including the first surprise of the evening, Silver Wheels from In the Falling Dark, rehearsed for the recent dates in Japan. Forty Years In The Wilderness, a fine song played as recorded on the recent album provided a stillness followed by the crowd pleaser that is Peggy’s Kitchen Wall. Bruce commented that Peggy Cade was originally from Liverpool. Cockburn introduced Café Society as a San Francisco song which, without the album’s harmonica or vocal distortion, was delivered with a welcome clarity. Bruce played Bone on Bone with a brighter presence than on the CD. Last Night Of The World was greeted with recognition by the audience and the first half closed with 3 Al Purdys, the project that kick started his song writing again after completing his memoir.

The second set opened with Bruce on charango for beautiful renditions of Bone in My Ear flavoured with sparkling windchimes and the most recent album’s Mon Chemin, a personal favourite of driving rhythm. Back to the six string Cockburn played Pacing The Cage as a request. Bruce continued to pile on the classic numbers and he played a beautiful harmonics solo to introduce If I Had A Rocket Launcher. Cockburn then swapped to the twelve string Manzer for Call It Democracy and a rearranged Jesus Train which I think I prefer to the skiffle take on the album, great guitarwork. Back to the six string and another disguised intro for Wondering Where The Lions Are. The second set concluded with the delay drenched If A Tree Falls and the surging momentum of The Gift revived for the band dates earlier this year. The audience had been very attentive throughout and were rewarded with three exquisite encores – One Day I Walk, World of Wonders (this rearrangement is light years from the original album take) and All The Diamonds In the World. It was a really satisfying show.

The Band on The Wall was also full, with a slightly more vocal crowd who sang along with gusto to Peggy’s Kitchen Wall and Wondering Where The Lions Are. Tokyo was substituted for Silver Wheels and Mighty Trucks of Midnight replaced Pacing The Cage. Unfortunately, shouted requests for any number of encores wrong footed Bruce who always has a plan. The crowd having settled, Cockburn played a beautiful (requested) All The Diamonds In the World however he then asked the audience to sing along to the unrequested Look How Far, a song I love. It didn’t quite work and I can’t remember in the past experiencing a Cockburn gig end on an indifferent note.

The venue in London is a fully operational church not really set up for concerts with stage lighting etc. A stage was erected in front of the altar and Bruce performed leaning against the organists bench. The pews were full, and the set list mirrored that of Liverpool. I am guessing that a large element of the audience was aware of Bruce through Greenbelt. The rather overexcited crowd not only sang along, at Bruce’s request, to Peggy’s Kitchen Wall and Wondering Where The Lions Are but also to some other numbers which rather marred the enjoyment of Cockburn’s performance for some of us. I was therefore fully expecting the barrage of encore requests. I think the “congregation” got what they wanted – One Day I Walk and Lord Of The Starfields. The latter was the only time this hymn like track was played over the three days.

Marco Adria made the following observations (in his book Music of our Times published by James Lorimer & Company Limited, Toronto 1990) “On a fall night in 1987, I went to hear Bruce Cockburn perform solo in Edmonton. Using only two acoustic guitars, a Chilean instrument called a charango on Santiago Dawn, and a set of wind chimes, he kept a sold-out crowd enraptured for two hours without an intermission. It had been several years since Cockburn had appeared solo. When he is accompanied by a band his voice and the artistry of his guitar playing do not shine as they do when he is alone. But what impressed me most that night - I’ve seen him in concert several times - was his ability to keep an audience with him for the entire performance.”

Over 30 years later Bruce is 73 and he now has a short intermission between the two, one-hour sets. He still keeps an audience with him for the entire performance. I had not heard Bruce play solo since 2015 and after the Liverpool show I contacted Daniel Keebler that night to report the show was so fresh and enjoyable.

Photos from Liverpool soundcheck by Richard Hoare

November 7, 2018

Southside Advertiser, Edinburgh

Bruce Cockburn

The Queens Hall Edinburgh

Review 7th November 2018

by Tom King

Bruce Cockburn performing at The Queen’s Hall Edinburgh tonight marked a long overdue, and welcome, return to Scotland as part of his current tour. For the Canadian born singer-songwriter this was also for him a welcome return to old family roots, and it was obvious all through the two sets of this concert that Bruce Cockburn was enjoying being here as much as his audience were enjoying him being here.

With a career spanning over 40 years, 100s of songs, and critical and commercial success, just where does a singer-songwriter of not only this depth of song catalogue, but quality of songs begin? Always a question as you can be sure that for every favourite in the set, someone’s favourite is missed out. Well, the most recent album, “Bone on Bone” from 2017 and a song from that album, “States I’m In” to open the set with was as good a place as any, and that blend of newer and older material continued throughout the two sets. Other songs from this album included amongst others, “40 Years In The Wilderness”, “Jesus Train” and a commissioned work on seminal Canadian poet Al Purdy, simply titled “ 3 Al Purdy’s”. Sometimes, listening to such wonderfully crafted songs and powerful lyrics it can be easy to forget at times just what a skilled guitar player Bruce Cockburn also is, and another song from this album, the instrumental title track “Bone on Bone” was a reminder of that laid back, but impressive skill.

Our second set opened with Bruce Cockburn swapping guitar for the not often seen here South American “Charango”, a stringed instrument with a very distinctive sound used with great effect on a few songs, “Pacing The Cage” being one of them. Earlier works including “Call it Democracy” and “If A Tree Falls” are striking examples of the music and words of Bruce Cockburn to tackle important issues like democracy and ecology head on and these songs are sadly more powerful and relevant now than when they were originally written, as the states of both democracy and ecology have only declined and worsened rapidly over the years .

So many classic songs here – “Silver Wheels”, “The Gift” and “One Day I Walk” being only a few of the classic songs from his earlier work that received well deserved applause, and that feeling of community that you sometimes get at a concert with so many people in the audience singing along to songs that obviously meant so much to them.

I have to admit that, although I was familiar with some of Bruce’s better known songs before this show, there were also many that were new to me, and a little online research ahead of this review just reinforced my opinions of his work. Bruce Cockburn is not just a songwriter, but a poet with the gift of painting pictures with his words, and what words! Older and more recent material clearly show a writer of strong opinions and principles, a writer not afraid to stand up and be counted whenever a voice is required on important matters of intolerance, social injustice, politics, the futility of war and ecology. It is clear through his music that Bruce Cockburn is still as relevant as a writer now as he has always been over the 40 plus years of his career.

Bruce Cockburn is a singer-songwriter-poet in the classic understanding of the term. Through his work you can hear the voices of other great wordsmiths including of course, Woody Guthrie and Bob Dylan. Bruce Cockburn has been an influence upon many songwriters over the years, and anyone listening to the early works of Bruce Springsteen will clearly hear that influence (amongst others) in his music.

Every generation needs someone like Bruce Cockburn to speak out for them, and new generations need to keep re-discovering people like Bruce Cockburn who have not only in this case left an important legacy of words and music for us all, but are continuing to speak out whenever needed through their works. It was nice to see such a wide spread of ages at this concert, proof that Bruce Cockburn and his music are still speaking to young and old in equal measures.

Bruce Cockburn took some time out from writing new songs for a little while a few years ago to write his autobiography (along with journalist Greg King). The book, “Rumours of Glory”, is probably the first stop off point now for anyone wanting to find out more about the life and songs of the man.

October 26, 2018

American Public Television

Songs At The Center

Cleveland, Ohio

The legendary Bruce Cockburn tapes "Master Series" episode for Season Five

Bruce Cockburn, one of the world's most celebrated songwriters, performs "If I Had a Rocket Launcher" during the taping of a "Master Series" episode for Season Five.

Bruce, winner of 12 Juno Awards and an inductee into the Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame - among countless other honors - taped the episode at the Beck Center for the Arts, in Lakewood, OH, following his sold-out concert the previous night at the Music Box Supper Club in Cleveland.

An Officer of the Order of Canada, Bruce just released his 33rd album, Bone on Bone, and is the author of Rumours of Glory, a memoir chronicling his life as a singer-songwriter, activist and spiritual leader.

Season Five will be released to national audiences in May, 2019.

October 17, 2018

The Cleveland Scene

In Advance of Next Week's Show at the Music Box, Bruce Cockburn Talks About the Spiritual Side of His New Album

by Jeff Niesel

Pacing the Cage, a documentary film about the career of Ottawa-born singer-songwriter Bruce Cockburn begins with a rather cryptic segment featuring U2 singer Bono talking about the power of Cockburn’s lyrics. Bono quotes the Cockburn tune, “If I Had a Rocket Launcher,” but it’s unclear exactly what he likes about the track.

“I had nothing to do with that,” says Cockburn in a recent phone interview when asked about the clip. Cockburn performs at 8 p.m. on Tuesday, Oct. 23, at Music Box Supper Club. “I can’t remember the occasion. It was a Juno Awards ceremony a while back or maybe the Canadian Music Hall of Fame. They solicited comments from various people like Jackson Browne and Bono and others. I think that’s what Bono did for that. I have no idea what he meant by [what he said], but he was kind enough to provide something, so there it is."

With its reference to Guatemalan refugee camps in Mexico, "If I Had a Rocket Launcher" generated a bit of controversy when it originally came out in 1984, but Cockburn, who says he discussed it at length when he performed it back in the day, maintains it wasn’t intended to incite violence.

“I thought about changing the lyrics, but I didn’t want to engage in any self-censorship,” he says. “I didn’t think it would end up on radio stations. When [manager] Bernie [Finkelstein] told me they would send it out to radio, I said that I thought it was stupid, and no one would play it, but they did. I hope people understood that they see it as an expression of frustration. I was worried about the reaction. I certainly wasn’t saying that we should shoot Guatemalan soldiers. I think more people understand it as personal rage or frustration than the people who knew it was specific and about Guatemala.”

Cockburn continues to nurture the political side of his music with his latest effort, Bone on Bone. The album commences with “States I’m In,” a tune that features Cockburn’s gruff voice and metaphors like “reality distorted like a sat-on hat.”

The material ranges from bluesy rockers like “Stab at Matter” to gentle ballads such as “40 Years in the Wilderness." There’s a Tom Waits-like quality to “3 Al Purdy’s,” a song that features spoken word, and songs such as "Cafe Society" and "Jesus Train" have a Dylan-esque quality to them. The album represents another solid effort from a guy whose music speaks to our troubled times.

Cockburn, who says President Trump is “completely worthless as a human being,” admits his feelings about the current political climate seep into some of the songs.

“‘False River’ is related to oil spills is related to the pipeline stuff that’s been going on,” he says. “The album is really more spiritually oriented, but you have to pay attention to these things that will have a profound effect on the world.”

The live show will find Cockburn performing solo, something he’s done throughout the course of his lengthy career.

“I always felt like it was an advantage to do solo shows,” he says. “There’s greater mobility when you’re by yourself and an ability to take things that come up on the fly. The logistics are simpler. The big difference is with the audience. I like having the band because there’s extra energy, and I can make a mistake – chances are people were paying attention to the drummer at that point. When I play solo, it’s a harsher reality but at the same time, focus is on the song and it’s front and center and I like that and the sense of one-one contact that comes with a solo show.”

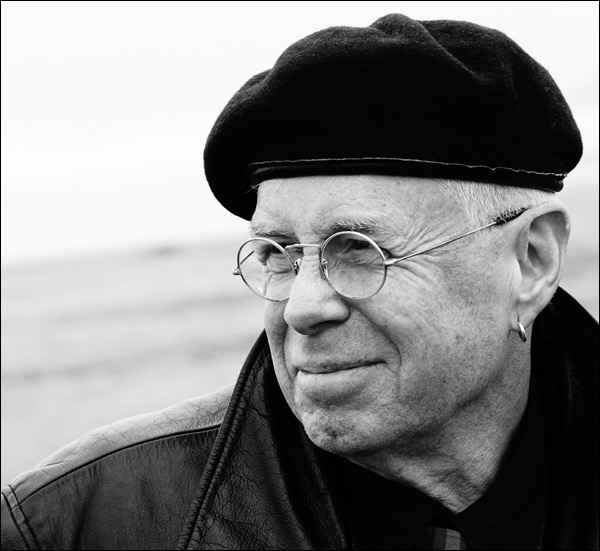

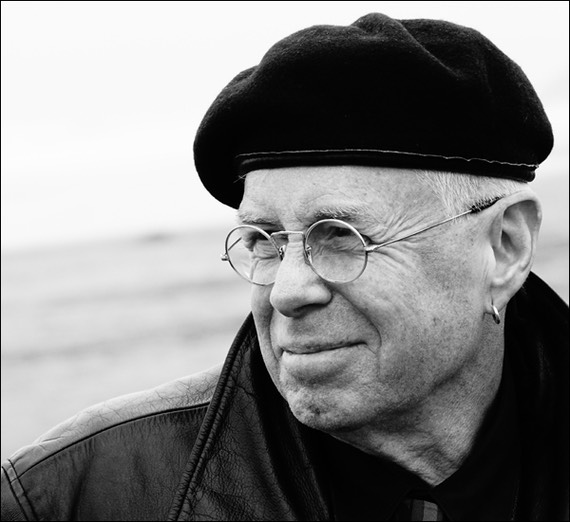

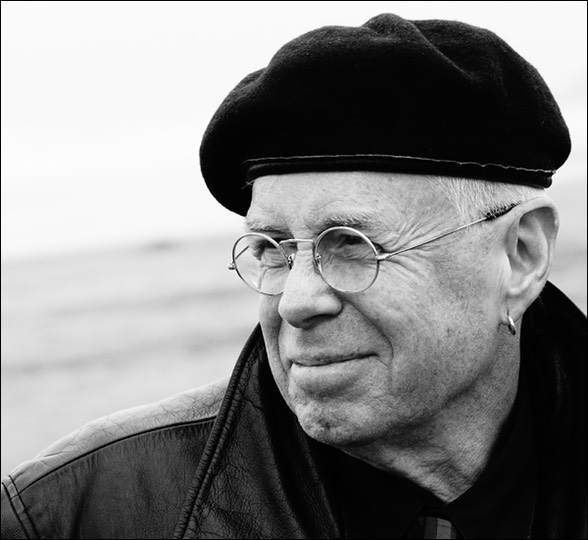

Photo: Daniel Keebler

October 15, 2018

Cleveland.com

Jazz-folk icon Bruce Cockburn brings 'Bone on Bone' tour to Music Box

by Chuck Yarborough

CLEVELAND, Ohio - For nearly 60 years, Canadian folkie Bruce Cockburn has been chronicling the world as he sees it, taking on oppression, the environment and just about any other topic.

CLEVELAND, Ohio - For nearly 60 years, Canadian folkie Bruce Cockburn has been chronicling the world as he sees it, taking on oppression, the environment and just about any other topic.

So where does the new release, "Bone on Bone,'' fit in the catalog of nearly 35 albums?

"It's the latest one,'' he said drolly in a call from his current home in San Francisco home earlier this month, ringing up to talk about his show on Tuesday, Oct. 23, at the Music Box Supper Club.

And then, because he's as honest as he is prolific, Cockburn explained.

"Where does it fit in terms of songwriting?'' he asked. "In a certain way, it's typical of my albums in that the songs reflect what I've been experiencing during the periods when the songs were being written.

"This case did not involve Third World travel,'' said Cockburn, whose most famous song arguably is "If I Had a Rocket Launcher,'' written about the starvation and oppression he witnessed during a trip to Guatemala. "There's a noticeable level of environmental commentary on this album, and the focus is more on the spiritual than anything else.''

Oh, and just in case you think he is either slowing down or cutting back, Cockburn preceded the 2017 release of "Bone on Bone" with a 544-page memoir called "Rumours of Glory'' in 2014.

The memoirs took three or four years of work, which cut into the songwriting time.

"All the creative energy I have went into the book,'' said Cockburn, who described the difference in writing for a book and writing a song as "night and day.''

"Writing a song is a short-term phenomenon,'' he explained. "You may spend hours on it, but a book requires you to focus on it for an extended period of time.''

What they do have in common, at least for Cockburn, is the personal aspects of each. While his songs may not be exactly about himself, they do tap his thoughts, beliefs, hopes and fears. Hints of "who" he is come through.

But a book, particularly a memoir, is a revelation of your own soul.

"Exposing too much of who I am?'' he said. "That was a concern. But the bigger concern for me was compromising other people. A lot of that didn't get said in the book.''

He's convinced that didn't affect the honesty of the memoir, not totally. But he conceded that putting in some details might have "altered the flavor of the book.''

"There are things I didn't want to say about my parents and other people who are still alive,'' he said.

Cockburn, not so surprisingly, used his catalog as the groundwork for the book, building the story of his life around the stories of his songs, because they are interwoven.

And now, he's sort of hooked, even though he's still putting out new music - and will until the day he dies, most likely. That's in part because songwriting is who he is, and in part because he feels the job of the songwriter is chronicle life itself. He's working on a book about medieval songwriters, even, and their role as the historians of their era. [Since the publication of this interview, Bruce said he is not writing a book on medieval songwriters. There was a miscomunication or misunderstanding about the subject. - D. Keebler]

"I think the job of an artist in whatever medium is to try to instill their experience of what it is to be human in some way that we all get to share,'' Cockburn said. It's a concept that has grown in the 73-year-old's mind and heart as the years have passed.

"That makes every face of the human experience subject matter for a song,'' he said. "It's perfectly legitimate to write silly dance songs or simple love songs - or not-so-simple love songs, for that matter.

"I think it's fair, and I personally like to write about everything I can,'' Cockburn said. "If I can find a way to make it interesting, it becomes natural.''

To that end, the current political climate is the perfect climate for a songwriter, especially one whose history is of activism and philanthropy.

And again, it's the "we're all unique together" mentality that makes it work.

"Everybody [poops], everybody's born. Everybody dies,'' he said. "What's to fight about there? On that level, it's really the sharing that matters."

Plus, a song - maybe one with a catchy melody or a clever lyric - can sometimes get through to an otherwise reticent person, almost without his or her knowledge.

"That's a great way to sneak in under people's fortifications,'' he said, laughing.

Posted: October 8, 2018

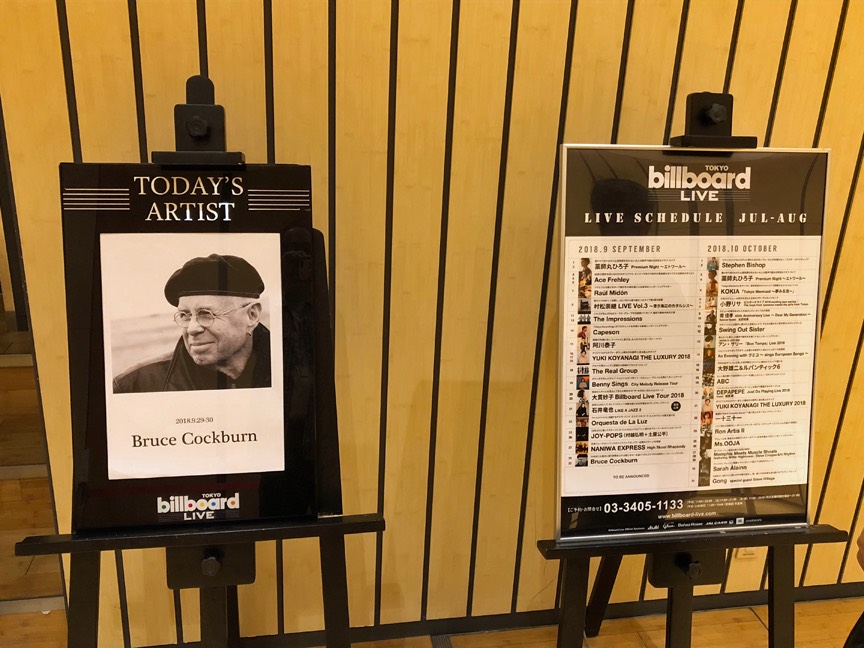

Bruce Cockburn Live in Japan

Takeshi Yamazaki has been following Bruce’s work since the early 1970s. He attended all four shows that Bruce performed at Billboard Live in Tokyo on September 29 and 30, 2018. He provided me with the setlist for all four shows. While taking photos during the performance was strictly prohibited, he did share a few that he took inside the venue before the shows. My big thanks to Takeshi for sharing this with us.

September 29, 2018

First Show

1. States I’m In

2. Lovers in a Dangerous Time

3. Tokyo

4. One day I walk

5. Cafe Society

6. Peggy’s Kitchen Wall

7. Bone on Bone

8. Bone In My Ear

9. Wondering Where the Lions Are

10. False River

11. If a Tree Falls

12. The Gift

Encore: All the Diamonds in This World

September 29, 2018

Second Show

1. States I’m In

2. Lovers in a Dangerous Time

3. Tokyo

4. Mama Just Wants to Barrelhouse All Night Long

5. The Iris Of The World

6. Bone on Bone

7. Mon Chemin

8. If I had a Rocket Launcher

9. Wondering Where the Lions Are

10. False River

11. If a Tree Falls

12. Waiting for a Miracle

Encore: Lord Of The Starfields

September 30, 2018

First Set

1. States I’m In

2. Lovers in a Dangerous Time

3. Tokyo

4. Forty Years In the Wilderness

5. The Iris Of The World

6. Strange Waters

7. Bone on Bone

8. Bone In My Ear

9. One day I walk

10. Wondering Where the Lions Are

11. Stolen Land

Encore: Mystery

September 30, 2018

Second Set

1. After the Rain

2. Last Night of the World

3. States I’m In

4. Lovers in a Dangerous Time

5. Tokyo

6. Cafe Society

7. Peggy’s Kitchen Wall

8. Bohemian 3-Step

9. Mon Chemin

10. If I had a Rocket Launcher

11. Wondering Where the Lions Are

Encore: All the Diamonds in the World

October 2, 2018

Billboard

Bruce Cockburn Plays First Concert In Japan For 26 Years

by Rob Scwartz

Legendary Canadian singer-songwriter Bruce Cockburn returned to Japan after 26 years to play a two-day, four-set engagement at Billboard Live in Tokyo on September 29 and 30. The guitarist and singer has long been connected to the country for songs he wrote in Japan when he visited in the 1970s.

Cockburn has been on a year-long tour supporting his 2017 album release Bone on Bone. The shows have seen him perform both with a band, and solo as he was in Tokyo.

Cockburn’s last appearance in Japan was 1992 when he was supposed to play and a huge Amnesty International benefit concert headlined by Neil Young. But due to illness, Young had to withdraw and the event was cancelled. Since Cockburn was already in Japan he played for the public at Tokyo FM Hall and an industry-only event at Canadian Embassy. Before that Cockburn had performed in Japan in the 1970s.

Japanese fans were clearly ecstatic that Cockburn was finally returning to perform live in the nation. All the shows played to enthusiastic packed houses. This is especially notable for the sets on Sept. 30 as Typhoon Trami was bearing down on Tokyo and many train lines were stopped. The streets were nearly deserted but you wouldn’t have known it from the full seats at Billboard Live. Cockburn performed on a steel string acoustic, a steel-bodied Dobro resonator guitar and a charango, a stringed, Andean folk instrument smaller than a ukulele.

The sets were a liberal mix of new songs and Cockburn classics, including “Lovers in a Dangerous Time” and “Peggy's Kitchen Wall.” After performing “Tokyo,” Cockburn told the audience “I wrote that song almost exactly 40 years ago… and I’m still here.” Paying homage to his bilingual Canadian roots, Cockburn performed the French track “Mon Chemin” and warned the audience that they might be baffled if they tried to decipher it as English.

Cockburn concluded the final set with one of his political tracks, “If I Had a Rocket Launcher,” about the killing of innocent civilians from the air in Latin America, and the U.S. radio hit “Wondering Where the Lions Are,” which peaked at No. 21 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1980. He came out for an encore of “All The Diamonds In The World” from his 1974 release Salt, Sun and Time.

Billboard Live, in the Roppongi district’s Midtown complex, is well known for bringing renowned acts with long careers to play in its relatively intimate setting.

Cockburn will continue the tour through February 2019 with nine more dates in the U.S. and seven in Europe.

Bruce Cockburn at Billboard Live Tokyo, 2nd set, Sept 30

1. After the Rain

2. Last Night of the World

3. States I’m In

4. Lovers In A Dangerous Time

5. Tokyo

6. Cafe Society

7. Peggy's Kitchen Wall

8. Bohemian 3-Step (Instrumental)

9. Mon Chemin

10. If I Had a Rocket Launcher

11. Wondering Where the Lions Are

Encore. All The Diamonds In The World

September 21, 2018

Canadian Folk Music Awards

The Gateway in Calgary, Alberta

November 30 & December 1, 2018

Bruce has been nominated in two categories:

SOLO ARTIST OF THE YEAR

Bruce Cockburn for Bone On Bone

David Francey for The Broken Heart Of Everything

Jolene Higgins (Little Miss Higgins) for My Home, My Heart

Catherine MacLellan for If It’s Alright With You: The Songs of Gene MacLellan

Buffy Sainte-Marie for Medicine Songs

ENGLISH SONGWRITER(S) OF THE YEAR

Bruce Cockburn for Bone On Bone

Lynne Hanson, Lynn Miles of The LYNNeS for Heartbreak Song For The Radio

Dana Sipos for Trick Of The Light

Noosa Al-Sarraj (Winona Wilde) for Wasted Time

Donovan Woods for Both Ways

Posted August 1, 2018

D. Keebler

Bruce was in Ashland, Oregon, in early July recording music for the soundtrack for a documentary film that is being produced by Les Stroud. In a May 2018 interview with Pamela Roz for Canadian Beats, Les said, "I also have a new independent feature documentary film I am releasing called La Loche. It’s a story based on the school shooting in La Loche, Saskatchewan, Canada in 2016 and about how nature can heal. The score is being done by Bruce Cockburn, along with some songs from Robbie Robertson, myself and orchestration and scoring by David Bateman."

July 20, 2018

The Sacramento Bee

Bruce Cockburn riffs on poetry, politics and an unlikely hit song

by Bill Forman

The traditional lullabies that parent sing to their children have sometimes been known to include disturbing images: babies in cradles fall from trees, children fear dying in their sleep, that kind of thing. But none, as far as we know, have involved assault weapons.

Until recently, that is, when singer-songwriter Bruce Cockburn was contacted by a fellow Canadian who’d made international headlines last October.

A revered singer-songwriter, Cockburn is best known for his unlikely mid-80s hit, “If I Had a Rocket Launcher.” According to “Rumors of Glory,” his 2014 autobiography, Cockburn had been visiting Guatemalan refugee camps, and after returning to a hotel room, was in tears as he wrote the song. While many who’ve heard the song may not be familiar with its back story, there was no overlooking the song’s infamous last line: “If I had a rocket launcher/Some son-of-a-bitch would die.”

“I was forwarded an email from Joshua Boyle, who I don’t know at all, but he’s the guy who was rescued from captivity in Afghanistan just recently with his wife and three kids,” the singer-songwriter said of the recent interaction. “He’s a Canadian guy who is married to an American woman, and they were captives of the Taliban for five years. And during that time, he sang ‘Rocket Launcher’ to his kids as a lullaby. They were just toddlers, so they wouldn’t get what the song’s about at all. But you could get what he was feeling, though – or, I can surmise at least, you know?”

Over the course of his career, Cockburn has won 12 Juno awards — the Canadian equivalent to the Grammy. Last year, he was inducted into the Canadian Hall of Fame last year, an honor that coincided with the September 2017 release of his 33rd album, “Bone on Bone.”

While it’s been largely underplayed in his music, Cockburn turned to Christianity early in his career, and, apart from a period in which he became fed up with the intolerance of the evangelical right, has remained so to this day. A rock musician whose music has incorporated elements of folk, jazz and world music, he’s been hailed as one of contemporary music’s most gifted guitarists, yet sings and plays in an understated way that complements lyrics that can be both poetic and polemical.

“On the coastline, where the trees shine, in the unexpected rain/There’s the carcass of a tanker, in the centter of a stain,” he sings on the new album’s poignant “False River,” while other songs slip in the wry sense of humor that sometimes rises to the surface: “Cafe society, a sip of community/Cafe society, misery loves company/Hey, it’s a way, to start the day.”

Taken together, the album is musically engaging and, in its own way, spiritually uplifting, something that will come as no surprise for his legion of fans. It also showcases his exceptional skills as a guitarist, as well as an occasionally more gritty side to his vocal style.

Cockburn talked about making the new album, the idea of releasing “Rocket Launcher” in Trump’s America, and what projects he would like to do in the future.

Q: How do you think the response to “If I Had a Rocket Launcher” would have been different if you released it today? I mean, that song was in heavy rotation on a lot of American stations, but the line “some son of a bitch would die” is a little extreme. I could see that sort of being quietly banned now.

I could see that, but I wouldn’t assume it automatically either, because I thought it would be banned back then. Like when it was suggested that it be sent out to radio stations as a single, or as the lead track from the album, or whatever it was, I said, “Nobody is going to play that, like, this is ridiculous.” And yet we know what happened. But the thing is, I think actually, if anything, it might even be more popular now, because everybody’s mad. I mean everybody is overtly angry now. And back then, it wasn’t popular because so many cared about Guatemala – I mean, there were those who did – but I think a lot of people liked it because it was an expression of outrage, of a sense of what they would feel as their own rage at life.

Were there specific circumstances that inspired you to write the song “False River”?

There were, but they’re not what the song describes. It’s a composite of images having to do with that kind of stuff, but the trigger for the song was a request from a woman named Yvonne Blomer. She’s the poet laureate of Victoria, British Colombia, and she put a book together of environmental-related poetry as part of the movement specifically against the pipeline that they want to put right close to Vancouver there, across the Rockies. There’s another one further north that’s also very contentious and probably will, sooner or later, go through. I mean, eventually they usually win. But there’s a lot of opposition to put both of these in. So she asked if I would contribute a poem. And I don’t really write poems, but I thought, well, maybe I can do this?

All you have to do is leave out the music and that makes it a poem.

Well, that sometimes is true, and I think in that case, it was. Most of the times if I were writing for the page, it would look a little different, because you do a lot of things for rhythmic reasons you wouldn’t necessarily do for the visual on a page.

But, in my mind, when I was writing that song, I had a kind of hip-hop rhythm, which informed the pacing of the lyrics. So it was written as a poem for that collection, but it was obvious to me, even before I finished it, that I was probably going to try to make a song out of it. And so I did so.

A number of your vocals on the new album feel bluesier than usual, even though the music is still kind of all over the place. How do you view this album musically, especially in light of the 30 or so that came before it?

I don’t spend much time thinking about that kind of comparison, but it’s kind of where I’m at now – whatever that means. The lyrics invite the music for the most part. There are other decision-making factors, but a set of lyrics will tell me whether they want to be performed on an electric guitar or an acoustic guitar, or whether they want to have a certain kind of rhythm. So a song like “Cafe Society” just wanted to be bluesy.

So after this tour, what will your next recording project be?

There are no plans to record right away – this album hasn’t run its course and I’m still feeling good about singing these songs – so that’s it for the time being. But two things that we’ve talked about doing as long range, somewhere-down-the-road projects are another instrumental album. We did one called ‘Speechless’ a few years ago that was a mixture of new pieces and previously recorded ones, and we might do a volume two of that, which I would quite like to do. And I’d also, if I don’t die first, like to eventually do an album of other people’s songs. But I don’t know.

Any artists in particular?

No, lots of different people. People that I admired. (Bob) Dylan would be there, and Elvis (Presley) would be there, and whatever other things I might dredge up from the depths.

July 19, 2018

Wentacheeworld.com

Bruce Cockburn continues his ‘journey of life’ | Singer-songwriter to play “Music in the Meadow” series

by Bridget Mire

Folk rocker Bruce Cockburn refers to his songs as his children, and it’s hard for him to pick a favorite.

On his latest record, he likes “False River,” which has a spoken-word vibe and warns about pipelines. He also enjoys the bluesy “Café Society,” about people who gather at a coffee shop to discuss global affairs.

“But, you know, when I start naming them, I start thinking, ‘Yeah, but then there’s this and there’s that,’” he said. “So, really, there aren’t favorites.”

A native of Canada and current resident of San Francisco, Cockburn has been in the music business for more than 50 years. “Bone on Bone,” his 33rd album, was released in September and won him his 13th Juno Award.

His career has taken him all over the world, and his current tour will include a July 28 performance at the Icicle Creek Center for the Arts in Leavenworth as part of the center’s “Music in the Meadow” series.

Cockburn took a break from writing music while working on his November 2014 memoir, “Rumours of Glory,” which took three years to complete. A box set of the songs included in the book was released at the same time as a companion piece.

The song “3 Al Purdys,” included on the most recent album and in a documentary about the late Canadian poet, got him back into his groove. In the song, Cockburn takes the voice of a homeless man reciting Purdy’s work.

Politics, spirituality and personal experiences all play into Cockburn’s music.

“It’s hard to pull out a single set of themes (on the latest record) that were deliberate,” he said. “I guess if you had to reduce it to some sort of capsule version, it would be just the journey of life. … There’s a fair amount of spiritual focus on this album compared to some of the ones I’ve done for a couple of decades. It’s never gone away, but it’s a bit more overt than it’s been for a while.”

He said he writes down ideas in a notebook as they come to him, sometimes as nearly complete songs and sometimes as just a line or an image.

“Very, very seldom have I sat down and said, ‘OK, I want to write a song about X, Y or Z,’” he said. “It just doesn’t work like that. I wait around, and I get an idea or something hits me in the face. Some horrible thing or some beautiful thing hits me in the face, and the juice starts flowing to get a song going.”

“Bone on Bone” is also the name of a song on the 2017 album. It’s a reference to arthritis, something 73-year-old Cockburn knows all about and an ironic title for a guitar piece.

Cockburn laughed as he remembered telling Michael Wrycraft, who did the album design, what he wanted to call the record.

“He said, ‘Oooh, sexy,’” Cockburn recalled. “He had no idea. I said, ‘Michael, it’s about having no cartilage left in your joints. If you think that’s sexy, more power to you.’”

Some fans like the music, he said, and others like the lyrics.

After a show in Italy that included songs like “If I Had a Rocket Launcher” and “Call It Democracy,” a fan approached him.

“He went, ‘Oh, I love your music. It makes me feel so calm, it’s like chamomile tea,’” Cockburn recalled. “I’m thinking, ‘I really got through to you, didn’t I?’ But that’s sort of rare. In most of Europe — or the parts of Europe I’ve played, like Germany and Scandinavia — most people speak pretty good English, so they know what the songs are about.”

Cockburn still hasn’t finalized his setlist for Leavenworth and said he’ll probably make decisions the day of the show. He knows he’ll have to include the classics people are familiar with but also wants to introduce them to newer material.

Although larger venues can be fun, he said he prefers smaller settings.

“It’s kind of nicer to play in a room where you can make eye contact with people and where it encourages people to listen with minimal distraction,” he said. “That’s more satisfying than playing a big, noisy event, although that can work, too.”

June 27, 2018

Now

The following is excerpted from the original article.

Last call at Massey Hall: fans and musicians share their stories

As the legendary concert hall darkens for renovations, we gathered memories from throughout the venue's 124 years

by Richard Trapunski

Prolific Canadian singer/songwriter Bruce Cockburn has recorded a live album at Massey Hall, 1977's Circles In The Stream, and is on the record as having played there 25 times – first in November 1972 opening for Pentangle and most recently this past May – but his manager and one-time Massey booker Bernie Finkelstein suggests that’s a conservative estimate.

Bruce Cockburn: Massey has always been one of those places that just seems like a milestone every time you play there. But my intro was not a positive one. I was in a short-lived band called the Flying Circus in 1968 that couldn’t decide whether it was the Band or Frank Zappa. We opened for Wilson Pickett at Massey Hall, and we were really just cannon fodder. The audience was there to hear Mustang Sally and In The Midnight Hour. They weren’t even slightly interested in our psychedelia. And then Wilson Pickett got held up at the border.

The PA wasn’t set up yet when we got pushed out on stage by the promoter, who said, “If you want to get paid, get out there.” So we started playing while they were still setting up our vocal mics and then the B3 organ blew up. There was a loud crack and a puff of smoke wafted out. The organist had to play the whole set on a clavinet. The audience was shaking their fists at us and screaming, “Come on, let’s hear some music!”

I went back four years later as myself and it was a lovely experience.

May 2018

Published in Sojourners

Dangerous Angels - Bruce Cockburn’s long, prophetic musical pilgrimage

by Brian J. Walsh

IF YOU WRESTLE WITH ANGELS, you will end up with a limp. When you struggle with God, engage the divine in lament-filled argument, cry out to the Creator for justice, hang on and refuse to let go without a blessing, you’ll end up with a posture bent over from the struggle and an uneven gait. Just watch Bruce Cockburn come onstage and you’ll see what I mean.

Known for hits such as “Wondering Where the Lions Are” (from the album Dancing in the Dragon’s Jaws), “Rocket Launcher,” and “Lovers in a Dangerous Time” (both from Stealing Fire), Cockburn’s evocative lyrics, exquisite guitar virtuosity, and unique blend of folk, jazz, and rock has brought him numerous awards and accolades over the years. More than 30 albums and close to a half century of touring would take its toll on anyone.

But there is more going on in the career of this Canadian singer-songwriter. The quiet Christian spirituality discerned in some of his early work was broken open in the 1980s when he first visited Central America. Revolutions and dirty wars in Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Guatemala opened his eyes to U.S. imperialism and the oppressive structures of global capitalism. Looking further abroad he became an advocate for ecological justice and the international banning of land mines. Closer to home Cockburn has railed against white nationalism married to the Religious Right while also passionately embracing the cause of Indigenous justice.

We haven’t heard much from Cockburn over the last few years. Writing his 2014 memoir, Rumours of Glory, took up so much creative energy that songwriting dried up for a while. But the muse returned, and the result is a new album, evocatively titled Bone on Bone: A reference on one level to the arthritis that afflicts Cockburn (though his guitar playing is still stunning), but perhaps more so to the wear and tear of a life of pilgrimage and a spirituality of resistance. A life of wrestling with angels.

No wonder he sings of an “aching in my hipbone” - that’s what happens when you contend with angels.

A price is paid for deeply engaging the world’s suffering, seeing what is just beyond the range of normal sight, and bearing witness. Walter Brueggemann writes that prophets offer “symbols that are adequate to confront the horror and massiveness of the experience that evokes numbness” as they “speak metaphorically but concretely about the real deathliness that hovers over us and gnaws within us.” The prophets, and their poetic singer-songwriter descendants, shake us awake when the powers-that-be prefer us to sleep. Many have recognized Bruce Cockburn as a prophet, even if he would demur at such a description.

When gloom and danger descend on the affairs of humanity, the dimming light can lull us to sleep. But in one of his most memorable lyrics, Cockburn sings that we’ve “got to kick at the darkness ’til it bleeds daylight.” One interpretation of this 1984 song, “Lovers in a Dangerous Time,” is that the evils done in Central America by the Reagan administration required aggressive resistance. In “Santiago Dawn” (World of Wonders), he dreams of the dawning of liberation in Pinochet’s Chile as the “creatures of the dark, in disarray / fall before the morning light.”

But Cockburn knows that externalizing evil thoughts and deeds, projecting them onto our opponents, is too cheap. We are all “hooked on a dark dream” (“Dweller by a Dark Stream,” Mummy Dust). In “The Whole Night Sky” (The Charity of Night), Cockburn sings, “derailed and desperate / how did I get here / hanging from this high wire / by the tatters of my faith.” Like a psalmist he confesses, “look, see my tears / they fill the whole night sky.”

But angels also move through the night. “Sunset is an angel weeping / holding out a bloody sword / no matter how I squint I cannot / make out what it’s pointing toward” (“Pacing the Cage,” The Charity of Night). Weeping over the violence of the day. Weeping, perhaps, in anticipation of the night. The artist cannot discern the meaning of the bloody sword. Later in the song Cockburn sings, “Sometimes the best map will not guide you / You can’t see what’s round the bend / Sometimes the road leads through dark places / Sometimes the darkness is your friend.” Perhaps that angel will reveal itself more fully after the sun has gone down.

Cockburn is right that we need to “kick at the darkness.” But kicking at the darkness without wrestling with angels, without contesting the state of the world with the Creator, is self-defeating human bravado. Cockburn knows this. No wonder he sings of an “aching in my hipbone” (“Open,” You’ve Never Seen Everything). That’s what happens when you contend with angels.

A price is paid for deeply engaging the world's suffering, seeing what is just beyond the range of normal sight, and bearing witness.

Now a denizen of the U.S., this Canadian singer-songwriter opens his new album self-reflectively with “States I’m In.” Old themes return as the song begins with the setting sun, a “curtain going up on the night time shadow play.” We are taken through a dark night of the soul replete with distorted reality, obsession, delusion, frustration, and vulnerability. But the night is not endless. Indeed, in the last verse we hear of “structures of darkness that the dawn corrodes / into the title montage of a new episode / whisper wells up from the deeps untrod / overthrows its channel and spreads abroad.” Whispers, rumors, dawn bursting forth. Kind of what we need these days, isn’t it? A new episode that will break the depressing monotony of what plays out on our screens and Twitter feeds.

There is deep spirituality on this album. Playing off the 13th century hymn “Stabat Mater,” Cockburn takes his place beside Mary, bearing witness to the cross. But “Stab at Matter” takes an apocalyptic turn as he bears witness to a world still hanging on that cross: “you got lamentation / you got dislocation / sirens wailing and the walls come down.” But there is hope in these falling walls. “You got transformation / thunder shaking / seal is broken and the spirit flies.” The empire might be imploding and the temples of our civic religion trembling, but all is a sign that “the Lord draws nigh.”

Some listeners will hear echoes of both Cockburn’s more explicitly Christian imagery of the ’70s together with the political edge of his repertoire from the ’80s on. But this is a political and environmental spirituality tried and tested by life on the road, the life of pilgrimage: temptations, dead ends, and miraculous moments of light and hope.

Whispers, rumors, dawn bursting forth. Kind of what we need these days, isn’t it?

Not surprisingly, there have been angels: “forty years of days and nights—angels hovering near / kept me moving forward though the way was far from clear” (“Forty Years in the Wilderness”). But this time the angels speak: “And they said / take up your load / run south to the road / turn to the setting sun / sun going down / got to cover some ground / before everything comes undone.” In this unspeakably beautiful song, Cockburn bears witness to the journey. You may be limping, bearing the scars of the struggle, bent over and tired, but there is another night coming.

You’ve got more ground to cover before it all comes undone. If that were it, some of us just might give up, say our bodies and souls can’t take anymore. But then, almost at the end of the album, Cockburn invites us onto the “Jesus Train.” In this driving gospel song, he sings, “standing on the platform / awed by the power / I feel the fire of love / feel the hand upon my shoulder / saying ‘brother climb aboard’ / I’m on the Jesus train.” Grace, my friends, pure grace. Can’t walk anymore? Are you derailed and desperate? Then get on board the train to the City of God.

Bruce Cockburn makes no pretense of being a spiritual guide, prophet, or even a conductor on the Jesus train. He’s simply bearing witness as a limping sojourner who is good company on this pilgrimage called Christian faith.

Brian J. Walsh is a Christian Reformed campus minister at the University of Toronto, adjunct theology professor, and author of several books, including Kicking at the Darkness: Bruce Cockburn and the Christian Imagination.

April 26, 2018

April 26, 2018

Stowe Today

Bruce Cockburn Channels Yeats

by Caleigh Cross

Looking out a hotel room window at a set of train tracks is apropos for Bruce Cockburn.

“There is a certain romance to that,” he allows.

Not just because he’s built a lifelong career on folk music, a genre that carries itself across steel tracks and rainy city streets at night, but because to Cockburn, the world is at a crossroads right now.

To Cockburn, the world is falling apart, and its future is slouching toward Bethlehem to be born.

“I don’t think that one should infer therefore that it actually is falling apart. That’s just how it feels. I can’t separate the thought processes that go with that notion from what might be the emotional impact of getting old. The world is falling apart for all of us one day,” said Cockburn, 72.

That feeling is threaded through the 11 tracks on “Bone on Bone,” the album the Canadian artist released last year after a six-year hiatus, during which he wrote a memoir, “Rumours of Glory.”

“When you reach a certain age, that falling apart, or at least your departure from that world, it looms larger on the horizon,” Cockburn said.

Even the album’s title is an acknowledgement that the center cannot hold — it refers to osteoarthritis, the condition that’s made it more painful for Cockburn to play his guitar as he’s gotten older.

As he sees more and more artistic greats racked up in the obituaries, he’s thought more about the kind of world from which he’ll one day fall away, he said.

“I can’t separate that from the idea that the world is coming apart. Having said that, I think that there is a very good chance that things are not going to make sense or be good in the world for a long time to come, and I’m not saying it’s the end of the world,” but “certainly the world that we grew up with is undergoing massive change, environmentally, politically, socially. There’s a lot of change going on,” Cockburn said.

“It’s moving very fast. I don’t think people are, I don’t think we as a species are keeping up with the pace of what we’ve thrown ourselves into,” he said.

Cockburn has historically been unafraid to take on topics such as pipelines, governmental hypocrisy and the way people live in his music.

His song “Café Society,” the fourth track on “Bone on Bone,” depicts lamentations of people in posh coffee shops bemoaning the headlines they read.

Something Cockburn doesn’t want to talk about? The President of the United States.

“Everybody has opinions about Donald Trump, to the point where it really doesn’t mean anything to express those views” unless they’re contributing to a meaningful discussion, Cockburn said. “People go on about his hands and how long his tie is. Who gives a shit? I haven’t talked about him because I think he gets enough attention. I don’t feel the need to write anything about him.”

“There’s no law that says anybody has to write songs about any particular topic. It’s just in your heart to write. If you don’t write what’s in your heart,” artists aren’t being genuine, Cockburn said, and music written that way won’t resonate.

A handful of the songs on “Bone on Bone” deal with Cockburn’s spirituality. He has an unwavering belief in God, and says he relies on it.

But he doesn’t think anybody’s faith should have a place in lawmaking.

“Your relationship with God is an individual thing. It’s how you personally are plugged into the cosmos. … The church doesn’t have the right to tell the government what laws to make.”

A belief that “there will be something that continues, and my relationship with God will be a meaningful part of where that is when I die” helps Cockburn navigate a world that’s shifted around him, and any outward expression of that should be loving.

“Our job is to love each other. That’s it. That’s all,” Cockburn said.

He’s been along the Route 100 corridor before, and is looking forward to playing for Stowe audiences at Spruce Peak Performing Arts Center Sunday.

“I’m really looking forward to being back in Vermont,” Cockburn said.

April 17, 2018

Style Weekly

Canadian Musician Bruce Cockburn Reflects on Awards, Political Songwriting and Faith

by James Toth

Bruce Cockburn was woke before many of us were born.

Throughout an enormously successful career spanning almost 50 years, 33 albums, a DVD, and an autobiography, the Canadian icon has used his music to advance humanitarian causes and support social change.

Back when pop radio was dominated by songs about uptown girls, Caribbean queens and wearing sunglasses at night, the politically outspoken Cockburn was writing controversial songs about imperialism and refugee camps. His latest album, "Bone on Bone," released in September, finds him comfortably taking on the role of elder statesman, his voice a little growlier but his writing and performing sharper than ever.

Style Weekly: Congratulations on your 13th Juno Award. Do career milestones still mean something to you?

Cockburn: They never really did. I like getting the attention that the awards bring, and as a measure of the fact that people are still paying attention after all this time. But I can't say that the work I do is done with the aim of getting awards. (Laughs.)

Your songs have often been very political, even during periods when it was considered unfashionable to sing about causes. We're at a cultural moment in which artists feel more comfortable than ever speaking out against social injustice. What's changed?

Circumstances. But the music doesn't go away. It does come and go slightly according to fashion, but the serious songwriters that take on issues have always been doing that. You could always go to coffeehouses or little bars and hear people singing songs about causes. Right now because of circumstances and general level of horror, there's a lot of room for that.

The lyrics to "False River" read very much like a poem, and you also have a song on the new record that is a kind of posthumous collaboration with Canadian poet Al Purdy. How important is poetry to you?

Very important. I discovered a love of poetry when I was in the sixth grade and it never left, and the way I choose to write my lyrics is very much influenced by the poetry I've read, and by what I've drawn from it in terms of putting words together. Al Purdy was a great discovery because I was aware of him for some time as part of the Canadian scene, but I never got into his work until the invitation came to write a song for this documentary (2015's "Al Purdy Was Here.") So I got a book of his collected work, and it was incredible. There is something so quintessentially Canadian about Purdy's poetry. It's not obvious in all of his poems, but it's certainly there, and I suppose that may have tapped some nostalgia button in me, having moved to San Francisco. It really resonated.

I know that song in particular was a catalyst for the writing of "Bone on Bone," after experiencing something of a dry spell while writing your memoir, "Rumours of Glory."

Well, it wasn't exactly a dry spell because there was a book, but there was about a four-year period where I didn't write any songs, and at the end of it, I wasn't sure I would write any. Not because I didn't want to, but because I just didn't know if the idea or the motivation or whatever it took to write songs was still there. But it turns out the invitation to do the Al Purdy song kick-started the writing process. Once I'd gotten that together, the rest of them just kind of came, in the old-fashioned way that they do.

You are a Christian living in a time of major societal upheaval. Does the state of the world ever test your faith?

My faith is constantly being tested, but it has more to do with me than the state of the world. It's just my own struggle to look beyond the immediate. For me, faith is a doorway to a relationship. And the door sticks, and that gets in the way of the relationship. And you can say it's a fallen world, and things like that, but the human psyche has this capacity for messing up and embracing a distorted view. We seem to have a better capacity for embracing distortion than we do for embracing clarity. So the struggle is to see things clearly and to me that clarity requires love, and invites love. For me, it's all about that.

March 25, 2018

Bone On Bone wins the 2018 Juno for Best Contemporary Roots Album of the Year

February 28, 2018

Wag

The Other Bruce

by Gregg Shapiro

Springsteen wasn’t the only important singer/songwriter named Bruce to emerge in the 1970s and continue making music to this day.

Canadian singer/songwriter Bruce Cockburn, whose debut album was released in 1970, recently released his 33rd album. “Bone on Bone” (True North), Cockburn’s first in six years, is a welcome return for an artist who has managed effortlessly to balance the personal, the political and the spiritual throughout his lengthy career. Additionally, in 2016, Cockburn added author to his list of achievements with the publication of his memoir, “Rumours of Glory.” I spoke with Cockburn in advance of his latest North American concert tour, which will bring him to Daryl’s House in Pawling, next month:

Allmusic.com calls you “Canada’s best-kept secret.” How do you feel about that?

“It’s an old thing. Millennium Records, who was the U.S. company that put out (my album) ‘Dancing In The Dragon’s Jaws’ in 1979 used that as an advertising slogan. These things never go away. I don’t think it applies anymore. At that time, it kind of did. Like any advertising slogan, it suffers from a certain glibness. It kind of had some significance then, but I don’t think it does now. There are areas of the U.S. where I’m not particularly visible or audible, but there are a lot of areas where I am.”

Six years passed between the release of your new album “Bone on Bone” and its predecessor “Small Source of Comfort.” In the “Bone on Bone” CD booklet, you list the years and cities in which each of the 10 songs was written.

“I’ve done that on all my albums. There was a long hiatus between albums, because I wrote a book. All of the energy that would have gone into songwriting, the creative juice all went into the book. There was that three-year period and then the year or so after the release of ‘Small Source of Comfort,’ where I was touring all the time. There was about four years where I didn’t write anything. At the end of that four years, I was thinking, ‘Maybe I’m a songwriter, maybe I’m not.’ It was a question of waiting to see if the book ‘distraction’ was out of the way, if the song ideas would come and they did, so we have a new album.”

The marvelous Mary Gauthier sings with you on “40 Years in the Wilderness.” How did that come to pass?

“We asked her and she said yes (laughs). That kind of overdub was done at (producer) Colin Linden’s studio in Nashville and Mary lives in Nashville. She happened to be there at the right time. We had a nice afternoon having her.”

The song “Stab At Matter,” which features the San Francisco Lighthouse Chorus, is a play on words on the title of the medieval Roman Catholic hymn “Stabat Mater.”

“I don’t even know when it started, but at some point I got this bug in my head thinking that the Latin phrase ‘stabat mater,’ which is ‘stand there, Mother’ …means a whole different thing (in English). There seemed to be an invitation in the English to make something out of it. It has this juicy quality to it. The spiritual side of things has always been a focus for me and I wanted to keep it in that realm. It’s not intended as a heavy philosophical statement, but we kind of (make an) exciting thing out of the notion of stabbing at matter.

“When one friend of mine first heard it, he thought it was kind of apocalyptic, because it talks about walls coming down, the seal being broken, the trumpet sounds. These are images we associate with the biblical apocalypse. I was thinking more in personal terms, one’s own spiritual state. It’s been my experience that whether you think of it in psychological or spiritual terms or a combination as I guess I do, we’re always invited to break down the structures that we build. If we refuse or ignore that invitation, they will be broken down sooner or later. If they’re not broken down with your complicity, it’s usually traumatic (laughs). ‘Stabbing At Matter’ was ‘Let’s get this sh– out of the way, let’s get down to it.’”

Poets aren’t often the subject of songs, but you pay tribute to Canadian poet Al Purdy in the song “3 Al Purdys.”

“That was actually the first of the bunch of songs to be written (for the album). I was waiting around for a good idea. I got an invitation from people in Canada, who were making a documentary film about Al Purdy, to contribute a song to the film. I didn’t have an existing song that would be appropriate. I thought, ‘This is great. I’ll say ‘yes’ and, if I get it together, then I do and if I don’t, then I guess I’ll prove to myself that I’m not a songwriter.’

“I don’t mean to make it sound so dire, but maybe there were other things I should be looking at. I wasn’t that familiar with Purdy’s work. He’s one of the great Canadian poets and I was aware of his existence. He died in 2000. He spent his youth, in the ’30s, riding the rails back and forth through Canada and became a more settled figure after that. He was a traveler with a sharp eye and a great gift for putting things into words. I was looking at this stuff and I got this image of this homeless guy who was obsessed with Al Purdy. The phrase, ‘I’ll give you three Al Purdys for a $20 bill’ came into my head. I pictured this guy ranting Purdy poems on the street with his cup out. I thought, ‘What else would he say besides Purdy poems?’ That’s what became the song.”

It’s been almost 35 years since the release of your songs “If I Had A Rocket Launcher” and “Lovers In A Dangerous Time,” and we are still living in a dangerous time. As an artist and activist, what are your hopes for the future?

“Oh, boy. (laughs) I hope I survive until my natural death at least. And I hope that my daughters and grandchildren survive. It’s really down to that. Survive in a way that’s recognizable. We can live like cockroaches, or we can have the lives of relative comfort and relative freedom that you and I have grown up with. These are things that should be treasured. It’s not a given to me that our descendants will be able to continue that for long. I hope they do. That’s what we should be thinking about. It blows my mind… the climate change deniers and the business-first mentality…make wild choices based on poor scientific information. Do the science and get it right and then take it seriously. We all need money. We all need to eat. You need to have an economy of sorts in the world, but an economy that’s based on, ‘It’s my right to get everything I want and screw you,’ which is what it is currently, is wrong. That’s self-defeating.

“You’re not just saying, ‘Screw you’ to your neighbor, who might not be as lucky as you. You’re saying it to future generations, as well. That makes no sense to me. I look at those things and I worry. But I also think there are grounds for hope. If somebody asks me where I get my hope from, I get it from a faith in God and life. I don’t think the God part’s misplaced, but the life part might be (laughs). But I have it anyway. We just have to pay attention, do what we can and then hope after that.”

February 16, 2018

Bruce Cockburn and Band in the Pacific Northwest, USA

Neptune Theatre, Seattle – Sunday 28th January 2018 (800 seats)

Aladdin Theater, Portland - Tuesday 30th January 2018 (600 seats)

Aladdin Theater, Portland – Wednesday 31st January 2018 (600 seats)

Review by Richard Hoare

The Bruce Cockburn band as a four piece, in support of the Bone On Bone album, started a forty-five date Canadian and US tour shortly after the release of that work on True North in mid-September 2017. This time Bruce is out on the road with Gary Craig on drums & percussion, John Dymond on bass and John Aaron Cockburn (Bruce’s nephew) on accordion, electric guitar and violin.

As Ron Miles played wonderful cornet on some of my favourite tracks on Bone On Bone I was apprehensive as to how those numbers would be re-arranged for the tour. At the same time, I was not aware until the tour started that John Aaron Cockburn was also going to play electric guitar and violin.

As the likelihood of Bruce bringing the band to the UK is remote I arranged to visit Daniel Keebler and Jerri Andersen in Snohomish and attended the shows in Seattle and Portland. I have known Daniel and Jerri for over 20 years and we first met in 1997, but this would be the first time we had attended the same shows!

All three shows were sold out. By the time the band reached Seattle they were cooking. Seattle was great, the first Portland show was better, and the second Portland show was even better. Daniel reports that the Grants Pass, Oregon show was outstanding, but we are getting ahead of ourselves!